Architecture profile: one to watch

Written by

08 June 2021

•

6 min read

For most of us, a map is a digital tool that allows us to navigate from one location to the next. But for architectural graduate Icao Tiseli, a map is a far more magical proposition—it’s not only for mapping physical data, but intangible information too.

She spends a considerable amount of time thinking and talking about maps, often to her colleagues at Jasmax, the architecture firm in Parnell, Auckland where she’s worked for the past two years. Icao admits her love of maps is now bordering on an obsession she occasionally needs to rein in: “I pick the times that I talk about maps—I’ve already annoyed everyone here!”

Intangible aspects of identity create belonging

Icao emigrated with her family from Tonga to Auckland when she was just nine. Moving from rental to rental, before her parents bought their family home, meant her experience of ‘home’ was tied to the way the family lived, rather than a physical location.

“The shell of the house wasn’t as important to me as the values and the customs and practices that we continued from house to house,” she says.

Those customs included planting seasonal crops and practising permaculture, just as they had in Tonga. These intangible aspects of identity led her to develop a unique perspective on people’s sense of belonging.

After highschool, Icao decided to study architecture—she’d always practiced art in some shape or form and the rational side of designing buildings appealed to her.

“I also never saw a Pacific person doing architecture so I just thought: what is this? What does this look like? So I stumbled into architecture purely because I was intrigued by it and I thought: ‘Let’s just give this a go’.”

Blurring the boundaries on the map

“Giving it a go” turned into postgraduate study and an NZIA Resene Student Design Award for her thesis project Mapping the Feke, in which Icao re-imagined the mapping of her ancestral land and investigated how mapping has been shaped by cultural perspectives.

The project was inspired by a minister she met back in Tonga, who was using a small dinghy to travel from island to island to do his shopping and to give sermons at different churches.

From the way he easily navigated the passages of water, Icao understood that his sense of belonging was not only tied to the land, but also to the ocean and that modern mapping failed to convey either the physical or spiritual connections at play.

“I thought: ‘Maybe the map should change in terms of conveying this relationship?’ Then the conversation was: ‘If I change the values of how a map looks, would that change how, as an architect, I investigate and draw ideas and information from the site?’”

By blurring the boundary between land and water, the understanding of ‘place’ is entirely renegotiated. For Icao, it also brings into question the permanence of the buildings in the landscape.

“Everything alludes to each other—the stars, the sky and the sea all flow into each other, which is to convey that all of these elements converge and nothing is permanent... This is how these people see their world, which is completely different to how we see ours.”

Remapping the way we use our spaces

So how does this transcendent understanding of place and mapping translate into Icao’s current practice at Jasmax? Quite beautifully, actually, because for Icao, mapping speaks to understanding a society’s values, which is never more important than in the practice of designing spaces.

One example of how she’s put this learning into practice is the recently completed Auckland War Memorial Museum’s new South Atrium, Te Ao Mārama, where many artworks of cultural and historical significance needed to be considered as part of the design.

“You understand the intention of what the artist is trying to create. You're the artist’s advocate when you go into figuring out the technical aspects of ‘How does this look?’ ‘How are we going to do the fixings?’ ‘What’s the strategic way of placing this here?’ You carry those intentions with you and the values of what this is supposed to be speaking to.”

Icao sees the caretaking role as applicable not only to honouring the space and the artist but also the public who visit the space.

“That is the duty of the architect, to take upon yourself to try and create a thoughtful experience but also an impactful experience for the user. And the user is [everybody]—it’s about disability access, it’s about being mindful of user experience, where you’re placing your exits... All of these things count and all of these things matter, and that’s the connection I've made between what I’ve learned and what I’m trying to practice.”

Integrating the Pasifika perspective

Icao hopes to bring her perspective to the design of more civic and public spaces in the future, and in the meantime is involved in a raft of initiatives to integrate a Pasifika perspective into New Zealand architecture practice.

Her passion for visibility and inclusivity of Maori and Pasifika people in the industry has led her to host talks both at Jasmax and art gallery, Object Space.

“It’s about including everyone in the conversation, but it’s also about doing the work itself together. That doesn’t befall a single group of minorities to lead the conversation and therefore bear the brunt of translating and being the sole advocates of it. It's about equipping everyone for it—and from that point on we can shift together.”

Icao not only talks the talk, she walks the walk. She’s part of a Tongan youth community outreach group, a member of Architecture+Women NZ, as well as a group driven by Pasifika women, called Maunga, which advocates for and fosters connections between Pasifika professionals and highschool and university students.

Continuous consistent motion creates beauty

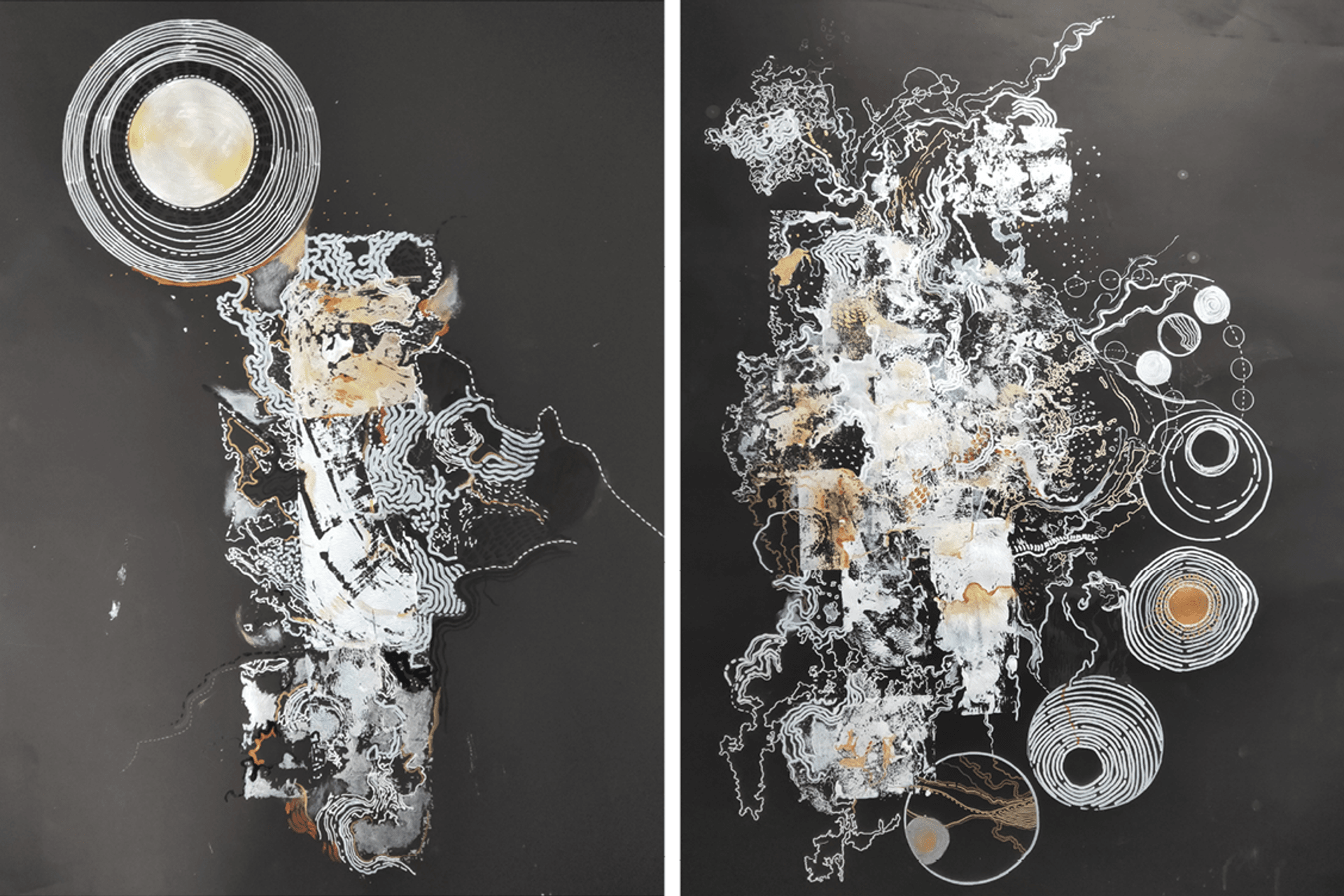

If that isn’t enough to keep the young architectural graduate busy, she also tutors at AUT and recently painted a mural at her local kindy. She’s keeping up her art practice of map-making and has plans to exhibit her ethereal works at Object Space, where she was an artist in residence last year.

It begs the question, does Icao ever take a break? She laughs and firmly says “No”, although she did take a recent trip to the South Island where she marvelled at the natural phenomenon of the Punakaiki pancake rocks—something of a metaphor for Icao’s own hardworking approach to architecture.

“The waves crashing onto the cliff are slowly carving out wonderful and beautiful shapes. I think that’s quite noble isn’t it? It’s doing the work when no-one’s watching and [also] when someone’s watching, but it’s that continuous consistent motion that ends up making beautiful things.”

Banner profile photo: David St George, Te Kāhui Whaihanga New Zealand Institute of Architects.