Designing a crystalline façade

Written by

19 June 2020

•

7 min read

Adding new life to the city

During the daytime, light dances across the twin-skinned façade of 2 Cathedral Square, highlighting a pixelated interpretation of the patterned slate tiles on the roof of the neighbouring Christchurch Cathedral. The contemporary pattern pays homage to this iconic Victorian Gothic building that was severely damaged in the Canterbury quakes in 2011 and is currently being restored. When the sky is cloudy the fritted pattern on 2 Cathedral is only just visible, but it comes to life when the sunlight plays off the surface and at night when colour-changing LED bulbs, that zigzag over the second skin, light up and enliven the streetscape.

As well as providing office spaces, the five-story building activates the street, offering ground-floor public spaces between Cathedral Square and the city's retail precinct with a spectacular atrium connected to high-end retail and hospitality spaces. Enveloping the building, the twin-skinned glazing hangs down like the hem of a curtain, creating sheltered public walkways and entrances around the perimeter.

Designing the twin-skinned façade

“Being engaged early on the project and attending regular design meetings in order to provide critical façade design guidance to the design team was highly valuable to all the key stakeholders, as we were able to provide system solutions and value engineering in parallel with the developing design,” says Thermosash’s Barry Davis – South Island, Contracts Manager.

“Designing and constructing this twin-skinned façade was complex,” explains Thermosash Design Lead Michael Phillips. “The outer skin is cantilevered both vertically and horizontally, projecting out from the building by up to three meters in places. The two façades are set apart to allow warm or cooler air to naturally convect between the two surfaces to assist in passively conditioning the air to the inner spaces.

"In this case, the geometry of the outer skin is predominantly made up of ‘folds’ in the façade creating large triangles, four storeys in height that are highlighted further with the integrated LED strips. The inner skin is a four-sided mechanically entrapped curtainwall composed of Thermosash PW400 IGU (Insulated Glass Unit) panels that spans between the slabs. The more complex outer skin is made up of the Thermosash PW1000 curtain wall suite and laminated single glass panes.”

"Everything on this building is bigger – bigger panels, bigger cantilevers,” says Michael. “We really stretched the engineering in order to deliver on the architectural intent."

Steel RHS (rectangular hollow section) needles had to be anchored into the slab face above and below the internal façade to support the external façade and allow the glazing to project out from the building.

“Along with the curtain wall, we also designed the skylights, a round window, the aluminium cladding, a couple of 4m-diameter DORMAKABA revolving door systems, and thirteen large glass auto-bi-parting Sensormatic sliding doors that are 1.5 x 3.5m on the ground floor," says Michael.

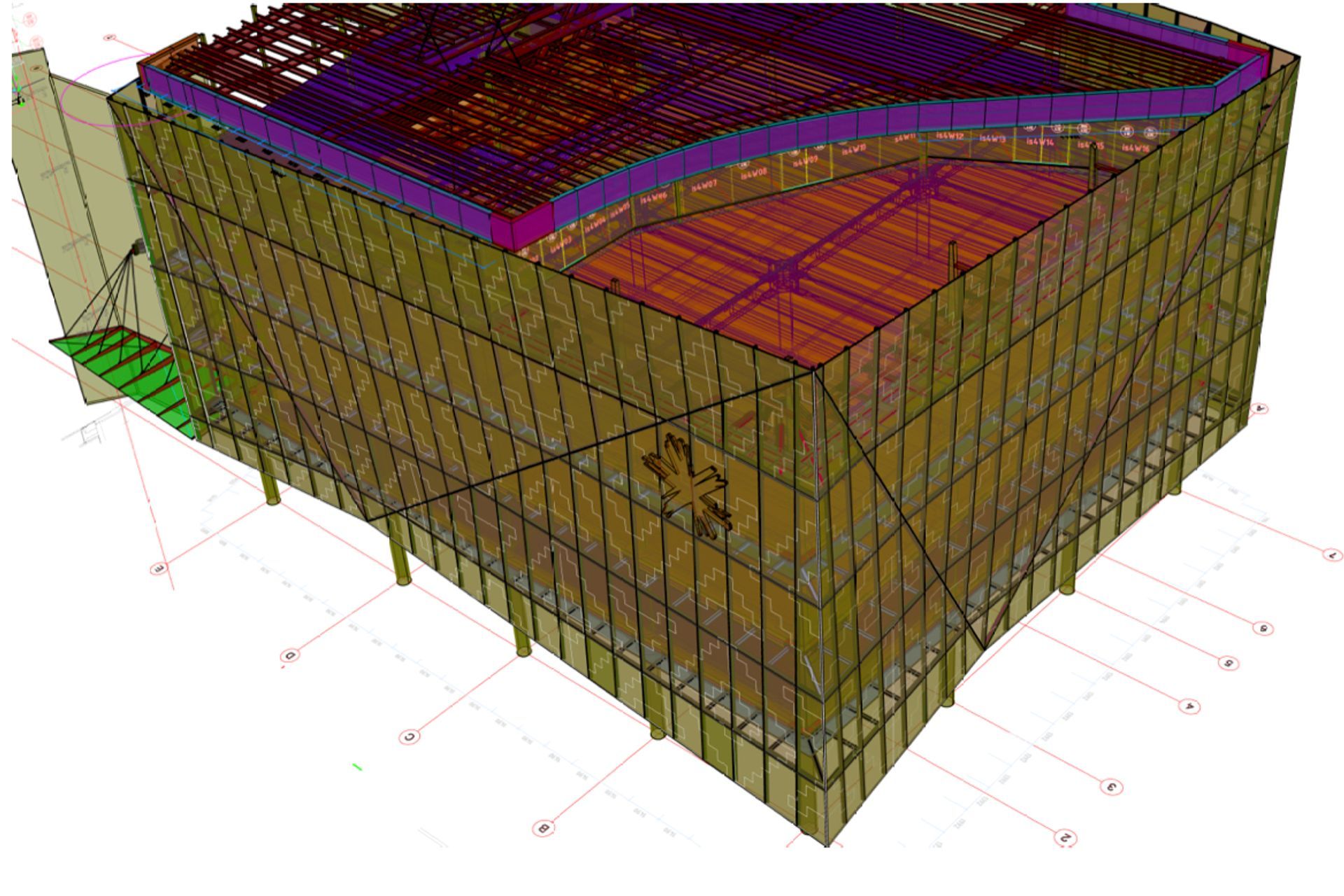

Due to the highly technical nature of the job, we had a team of Thermosash’s in house structural and façade engineers working on the project during the design phase. “Designing the second skin took the longest time. We designed the twin-skinned geometry component in three dimensions, utilising both AutoCAD and SolidWorks,” says Michael. “In addition, Thermosash developed some of its own 3D software that is used to develop complex façade solutions from beginning to end. Our in house technical team write code for us to achieve the desired results,” he adds.

Shrouding the whole façade in pattern

As well as paying respect to the Cathedral, the ethereal pixelated pattern over the surface of the façade references digital data—apt for its telecommunications occupant, Spark. The ceramic baked graphic ‘fritting’ contains a series of dots that increase in size to create the pattern, which, along with its aesthetic value, in a practical way, helps to prevent the interior from overheating during the summer. “We shrouded the whole façade in the pattern, then cut it up like a very complex three dimensional jigsaw puzzle,” says Michael. “It was extremely detailed and labour-intensive and a great test of our AutoCAD 3D skills.”

“It was a real challenge for the design team to make the ceramic fritted dots look like a pattern,” explains Barry, who oversaw the manufacture and installation of the façade and other glazed elements. “We worked through a number of prototypes for the ceramic graphics with the architects – including a version of the Cathedral’s Rose window. If we had created a regular glass façade, it wouldn’t have been so iconic, but the addition of the pattern that was selected that relates to the Cathedral slate tiling really adds something special.”

Solving wind load on the façade

Michael, the South Island Thermosash Design Manager, British-born and trained, has worked for Thermosash in New Zealand for 14 years. “It is more interesting working in New Zealand than in the UK as the conditions are much more dynamic―the wind pressures are higher, there are greater extremes of temperature and then there’s the seismic aspect, which combines to create a series of challenges that the Thermosash team manage and mitigate for our customers.

“Solving the wind load and seismic requirements was quite a big feat in terms of engineering,” says Barry, who has been with the Thermosash for 17 years. In the western end of the atrium, a 250mm-wide seismic movement joint has been inserted to help protect the building in the event of another substantial earthquake. “The 4.2m-high total vision glazed wall on the south face also required considerable complex engineered solutions due to the seismic and wind loads it has the potential to be subjected to,” he says.

Lighting the façade with LED

The outer skin incorporates LED lighting that highlights the triangular facets. “The LED lighting in the main part of the façade was developed in partnership with Aotea Lighting and involved a system of channels that makes the integrated LEDs within the façade appear seamless,” says Barry

The evolution of glass

The outer skin is a grade A safety glass made up of toughened laminated glass, making it resilient during earthquakes and extreme weather conditions. “The technology of glass changes all the time,” says Barry. “Part of the design development process that we undertook with the architects was looking at using standard clear glass, however, when we prototyped it with the dots in the fritted pattern, they looked green due to the iron in the glass so we then trialled low-iron glass, which makes the dots appear whiter.”

The low-E coating is an incredibly thin metallic film applied onto the glass in Germany from one of our tier 1 base glass suppliers. Low-E glass helps with reducing solar gain and also reducing heat loss thereby further reducing demand on mechanical conditioning equipment to keep the building comfortable for the users. The internal atrium also uses low-iron glass to create a highly transparent effect.

Thermosash is a family-owned company founded nearly 50 years ago, in 1973, and continues to manufacture and employ locally with its 570 team members throughout the New Zealand wide group, with its headquarters now in Auckland.

“The Spark second skin is unique but, then, every building has its own unique challenges,” says Barry. “We enjoy working with the architects to achieve what they have conceived and have made ourselves adaptable in that way, but the team enjoys that and is probably why our staff turnover has been low over the past 17 years that I’ve been here. The impressive and often complex designs we are given from architects and engineers that we have been realising for our customers is our point of difference and keeps us all driven to keep delivering specific engineered facades for another 50 years.”