Passive solar design vs. Passivhaus

Written by

29 February 2016

•

5 min read

Many New Zealand architects are looking to satisfy a particular desire among many home owners and developers. Today, more people than ever before want to have as low an environmental impact as possible.

A testament to this is the World Green Building Week in September, with events held in countries throughout the globe including all over Aotearoa, to educate people on how sustainable building can be developed. Typically, the standard in place to measure green design and energy efficiency is Homestar for residential projects and Green Star for commercial projects. These are criteria laid out by the NZ Green Building Council, though there is a growing consideration that more could be done.

Solarei is one of the architecture and design firms leading the way in environmental housing that also combines breathtaking modern design practices. The company's founder, Duncan Firth, spoke to us recently on two of the most promising and prominent methods for creating a comfortable, green and modern home.

Passive solar design is the first, and can be seen in many NZ homes, while Passivhaus is a newer concept, yet to be completely embraced by the Kiwi population. So, what are the differences between the two? Duncan shone some light on the matter.

What is passive solar design?

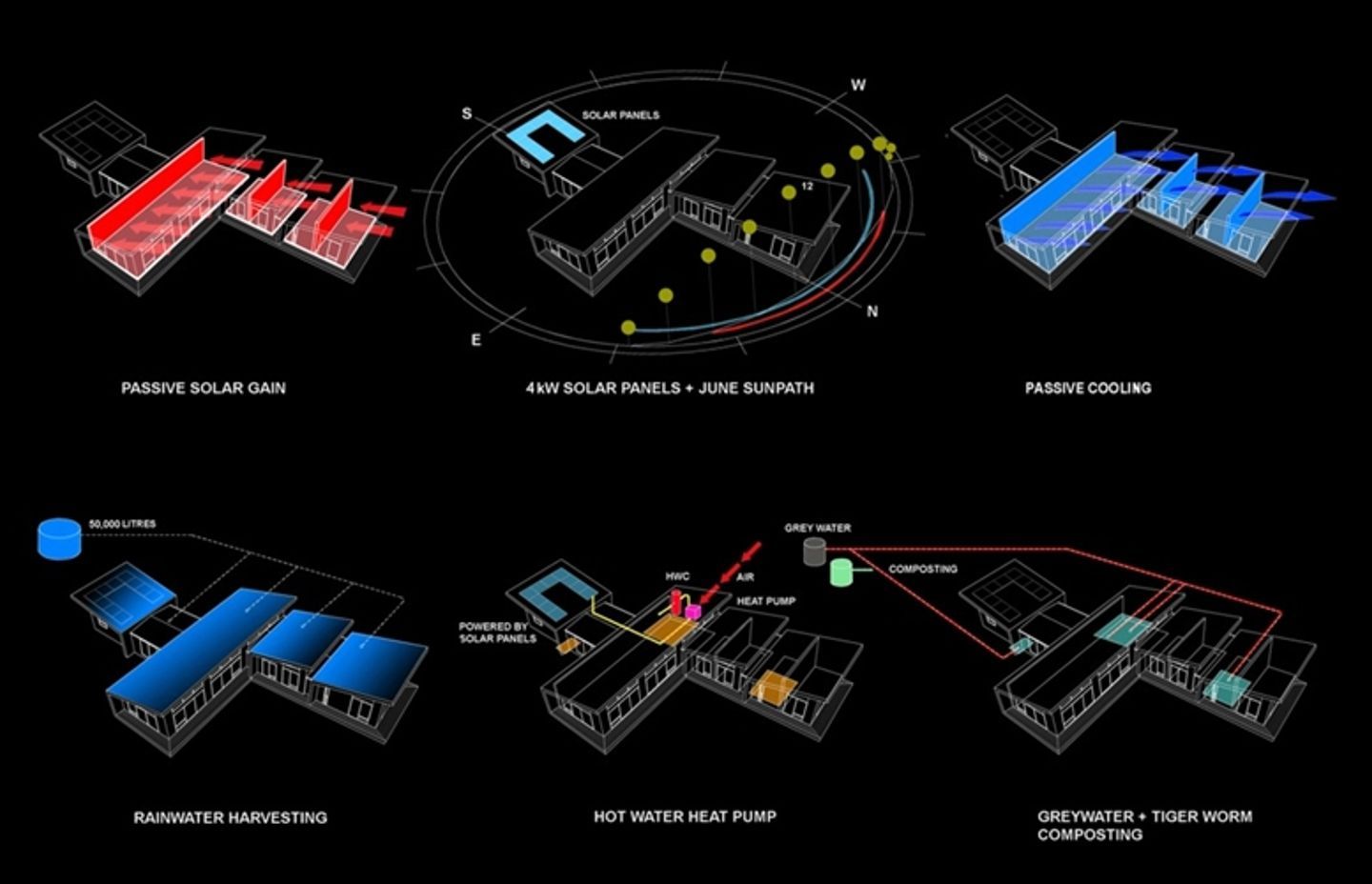

New Zealand's geographic location is perfect for natural heating and ventilation. To this end, passive solar design is the use of sunlight and natural air flows to respectively heat and cool a house without relying on mechanical devices, heating systems and other machinery that use electricity.

Thermal mass (concrete) is the key ingredient and is able to store radiant energy from the sun (heat). The heat is then released when temperatures begin to cool.

Sunlight is captured throughout the day and held in the building's thermal mass, making it warmer in the colder months. When summer comes around, New Zealand's prevailing winds and natural air flow can be used to naturally ventilate and cool a building.

Typically, air enters the house and as it heats up it leaves through top light windows, strategically located at high points at ceilings to allow warm air to exit the building. Duncan likens the process to a set of lungs, providing constant fresh air to the home's occupants.

However, it also takes a good understanding of the local weather and meteorological patterns, as Duncan explains.

"Environmental design is really understanding the unique nature of each specific site – understanding how the seasonal sun paths work, how the prevailing winds blow, and even really simple things like whether there's a mountain or hill that blocks the sun during winter," he began.

"The whole idea of passive solar is creating a house that unlocks the potential of the environment. The house is designed to follow the seasonal sun paths so there's a constant presence of sunlight in the building, from early morning to sunset.

"In summer, it's designed for cross ventilation, stack effect, and other natural ventilation strategies that keep the house cool."

What is Passivhaus?

Passivhaus is a concept created in Germany. The very first building of its type was built in Darmstadt in 1991, and since then more than 30,000 buildings around the world have been designed and constructed to this standard. Passivhaus is recognised as the international standard for passive design techniques. Duncan delved into the specifics.

"It's relying on a very well-insulated thermal envelope and also achieving a high degree of air tightness within the building. In Passivhaus, you don't lose air from inside the building. The idea is if you can keep the air within the house, the sunlight and even the occupants can create warmth without relying on mechanical heating," he told us.

"There's a very stringent set of criteria that they use. Passivhaus homes don't necessarily need to face directly north for passive solar gain. It's a very good strategy if the house is on a site that faces south and cannot get much sunlight throughout the day. It's very good when you don't get that exposure."

Whereas passive solar can rely on natural ventilation, Passivhaus designs rely on a small mechanical fan to circulate the air – one distinct point of difference for those looking at building a green home.

So, which is better?

"In essence, both Passivhaus and passive solar design have similar aims: to reduce energy usage and achieve good health and comfort for the occupants. I wouldn't say that one is better than the other, both approaches work together very easily – in certain situations one is clearly more beneficial and but it depends on a number of factors," Duncan concludes.

"What has changed in the past 20 years is technology. Technology gives very clear meteorological information about specific environments; it has given us insulated concrete slabs, insulated glass window, increased levels of insulation for walls and ceilings, and the ability to achieve airtightness inside a home. All these factors have further advanced passive design strategies around the world."

Passivhaus is very new and is really still proving itself in New Zealand. We're still yet to understand whether Passivhaus is suited for the country's climate characteristics, as well as the budget requirements for Kiwi construction.

Ultimately, the choice between the two sustainable building methods is one that depends on many factors – not least of all location and budget. When it comes to making a truly energy-efficient home, however, there is no question: one should always rely on the experts.