Rethinking our windows—the case for using uPVC in New Zealand

Written by

21 July 2021

•

5 min read

When temperatures are consistently below zero in winter, insulation and maintaining heat is critical, not just for comfort, but for survival. Window frames in Europe are commonly uPVC because its performance far exceeds that of aluminium, as well as being far easier to maintain than timber.

“uPVC windows have been used in Europe for 40 years now and have continued to grow in popularity as more and more people come to realise how good they are. And they’re not being replaced, but updated, with newer versions of the same products, using innovative designs and technology. No one goes back to the old windows once they’ve had them.” says Martin Ball, Managing Director of Christchurch-based NK Windows.

A trend that is beginning to find purchase here in New Zealand as well, he says.

“We’re seeing a range of people coming to us: there are Europeans who are now living here who demand the same warmth in their homes that they’re used to in their home countries; we’re seeing kiwis who have lived, worked, or travelled through Europe and have experienced just how good these windows are; and, we’re seeing younger couples looking to build smaller but better, along with older couples who may be doing the same but for different reasons—and both groups research properly before settling on uPVC.”

uPVC: the environmentally friendly, energy efficient window option

A typical response is to question whether a product made from uPVC can be environmentally friendly.

In fact, uPVC is a by-product of chemical processes used within the petro-chemical industry, turning it into window frames helps reduce plastic waste. They also use far less energy to produce and they’re incredibly energy efficient, so overall they have a very small carbon footprint in terms of both production and ongoing use.

Furthermore, most of the materials used in uPVC windows are recyclable and European standards demand new windows contain a high component of previously used material, so they’re one of the least carbon-footprint impacting products you can use in your house.

The Zero Energy house, in Auckland’s inner-city suburb of Point Chevalier, is the perfect example of a house that maintains a constant internal temperature throughout winter without needing much additional mechanical heating. Its use of uPVC windows is a key part of achieving that.

“A quarter to a third of all heat loss from a home is through the windows, with about 25 per cent due to the frame. The uPVC windows in the Zero Energy House have an R rating of around 1, versus a normal single-glazed timber window at just 0.25—making the uPVC window 300 per cent more efficient. Heating costs for the Zero Energy House are regularly less than $50 per month in winter, and sometimes nothing.

“Drapes can help mitigate heat loss, but our single-glazed, aluminium-framed windows are simply ‘heat exchangers’. Anyone standing next to a traditional window in winter can, quite literally, feel the heat being sucked out through it,” says Martin.

uPVC windows come triple glazed and the frames themselves are incredibly thermally resistant. That’s why they’re used at New Zealand’s Scott Base in Antarctica.

In addition to the prevention of heat loss, uPVC windows provide a warm surface, so moisture doesn’t form on the frames, which means mould is unlikely, too.

“Anyone wanting to build in an environmentally-conscious way has to consider uPVC windows. And once they’ve got their finished home, they’ll enjoy the warmth for the length of their occupation. It really changes people’s lives.”

uPVC: offering form and function

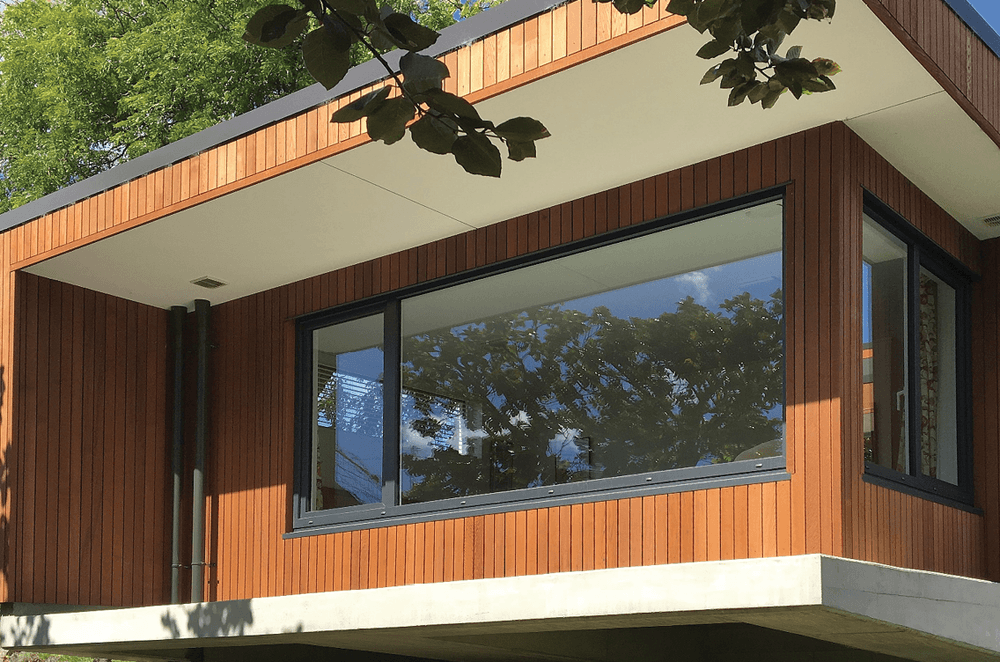

The aesthetics for uPVC are also different. The lines are not as sharp as they are on aluminium joinery but they mimic the lines of traditional timber joinery better than aluminium and are often a better option for replacing windows in older homes.

An aluminium skin can be added to the outside of the frames if desired, in order to better match existing cladding or to give that aluminium look, or a ‘timber’ foil can be used instead, with a choice of different timbers, to mimic a wooden window frame look. Different colours can be used on each side, or any combination of ‘timber’, aluminium or colour can be created.

Colour is created by adding coloured laminate directly to the uPVC, so it’s bonded to the material rather than acting as a coating, increasing its longevity and there’s next to no maintenance as there is for wooden window frames.

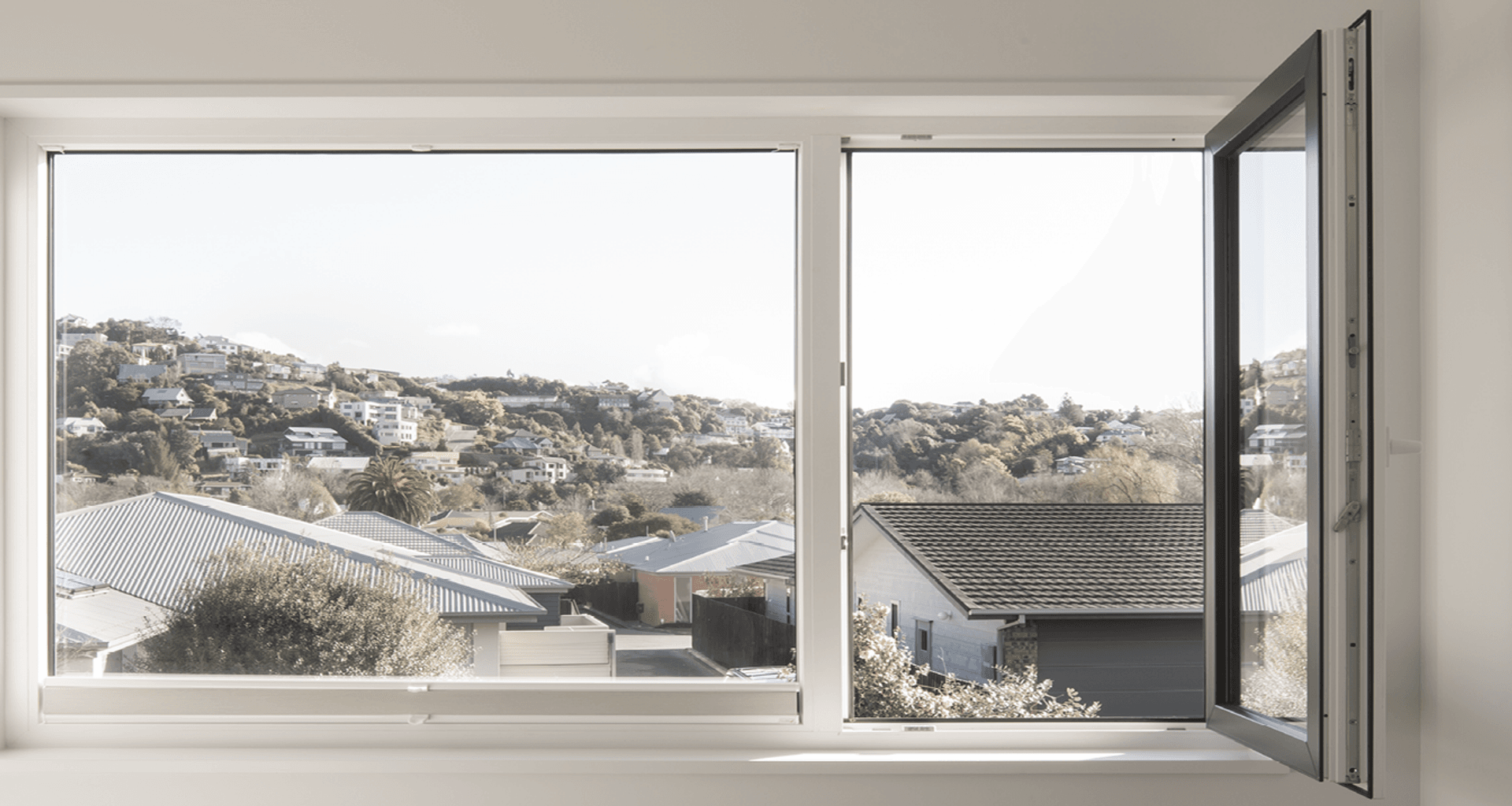

Another key difference is that, coming from Europe, they can feature a tilt and turn mechanism. European windows tilt inwards with the ability to hinge at the base, giving passive ventilation but added security, or, by turning the handle a different way, they can open inwards like a traditional casement window.

Although uPVC doesn’t have the strength of aluminium or wood, windows made from it can still be built to 2.8m by 10m sizes for sliding doors—easily big enough for most houses.

NK Windows is based in Christchurch and has installed windows in homes throughout the South Island. They are now also exploring opportunities in the lower to central North Island and Martin says they’re getting interest from people wanting to build above the current Building Code.

“The Ministry of Building, Innovation and Employment is currently reviewing the code, with a strong likelihood standards will be raised closer to European levels.”

Learn more about how uPVC windows can transform your home.