Hunkered into the hillside and seemingly floating over a pond, Hidden Island Retreat enjoys panoramic views of mountains, lakes and tarns, rocky alpine outcrops and tussock grasslands. Designed by Francis Whitaker of Mason & Wales Architects, in collaboration with his colleague Hamish Muir, Hidden Island Retreat is a powerful composition of architectural form and materials to ensure it sits comfortably within one of the most beautiful landscapes in New Zealand.

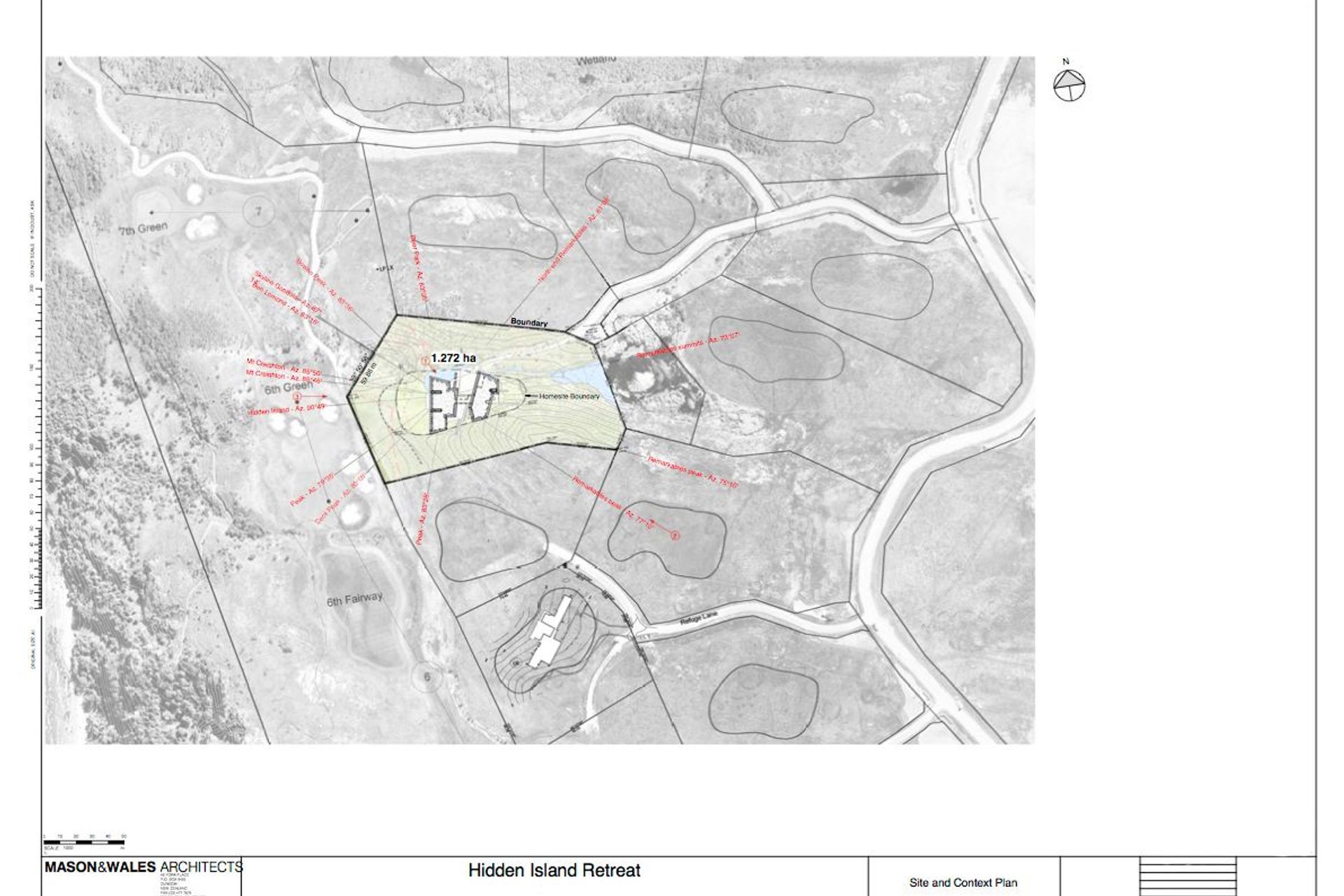

On an exposed site near Jack’s Point Village, just 20 minutes from Queenstown, this modern home has been designed to capture views in all directions, due to its location at the foot of The Remarkables mountain range, beside the shores of Lake Wakatipu and next to an 18-hole, par 72 championship golf course. In Queenstown’s district plan, the area is officially described as an ‘outstanding natural landscape’, which meant that the design and construction of this project required extra special consideration.

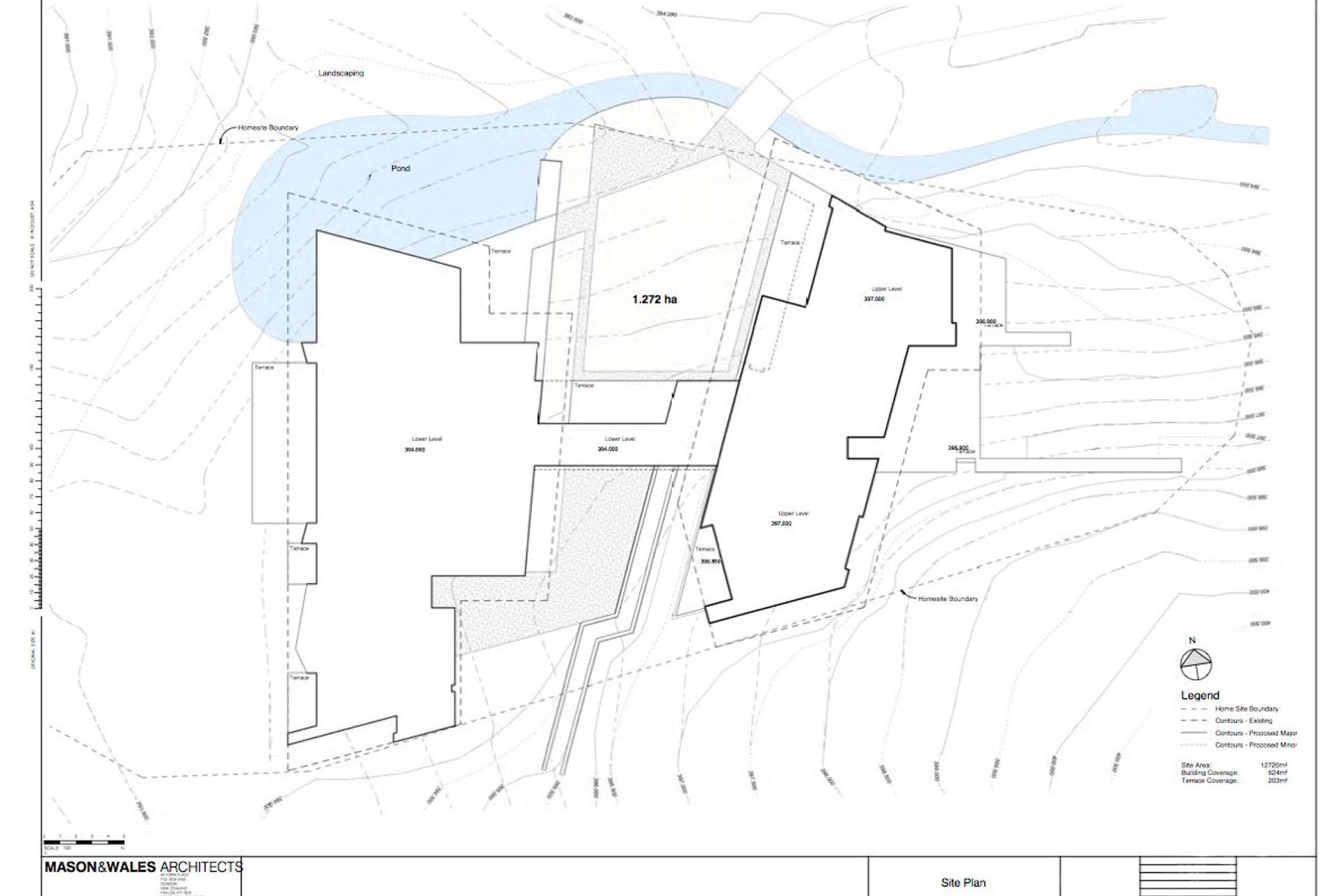

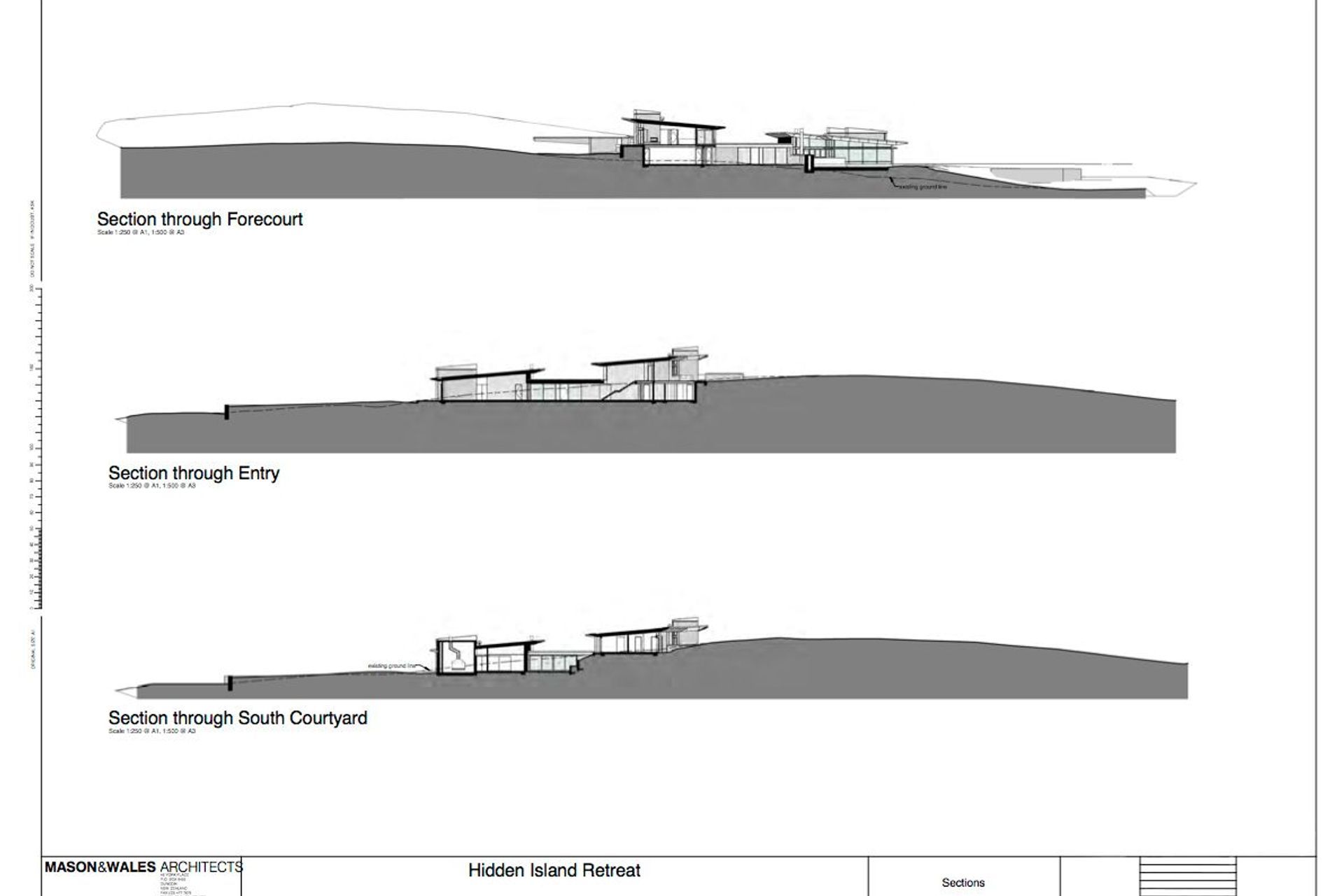

At 800m² in size, Hidden Island Retreat is a particularly large house, plus there is another 200m² of terraces and decks, so its form and materials needed to be discreet and recessive when viewed from neighbouring properties, the golf course, and from the lake, mountains and sky. “The architectural language and material palette responds to and is subservient to the natural landscape,” explains Hamish. “We’ve cut the house into the hillside to minimise its height so it fits in with its surroundings.”

Using recessive colours on the exterior – in warm brown and grey tones, rather than black – has helped to blend the form into the tussock grasslands, the native vegetation and the mountainous backdrop. “The design ties in with the craggy landscape and the jagged edges of the mountains. Stone, metal, wood and glass help to create a composition that sits harmoniously in the landscape,” adds Francis.

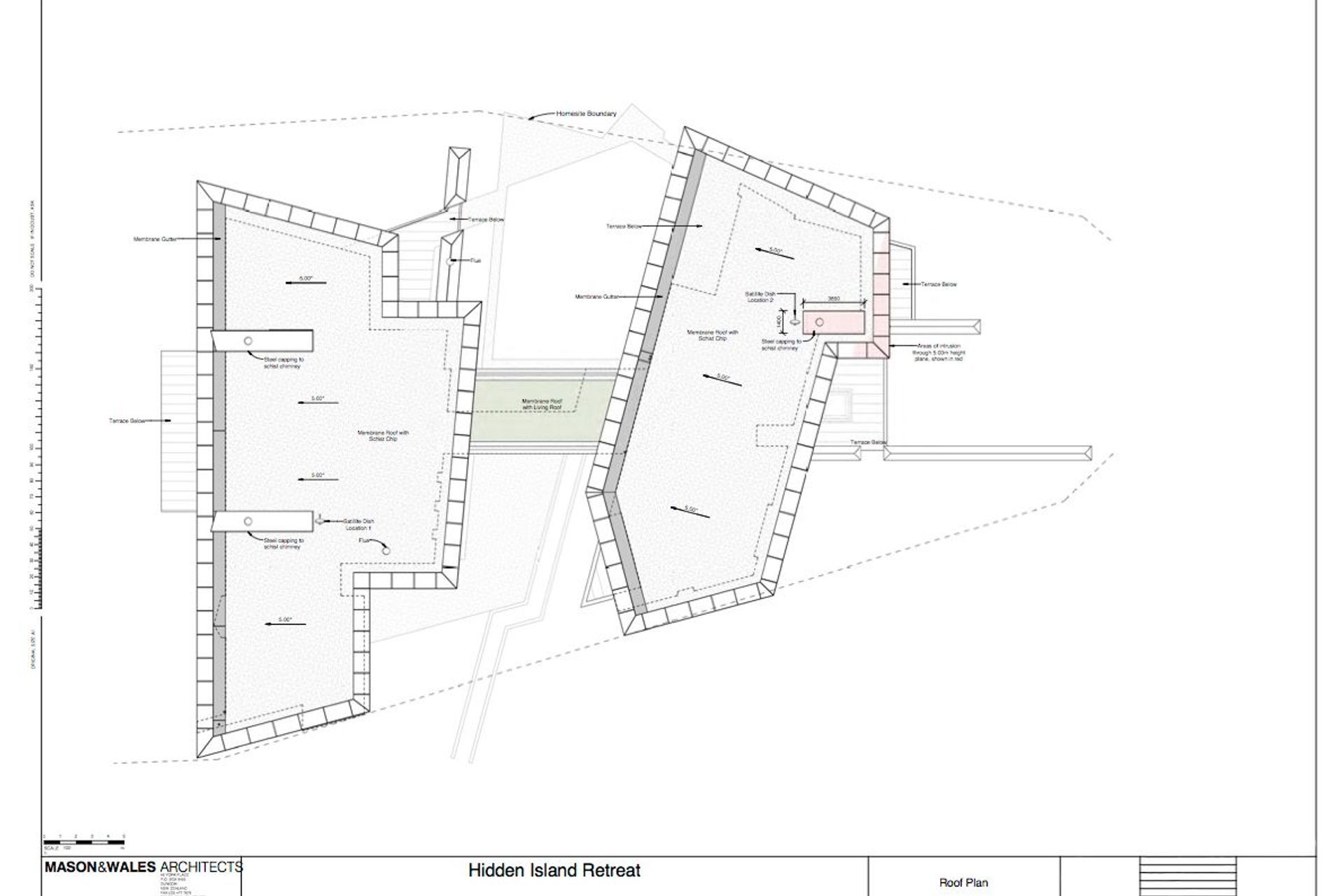

Excavating into solid rock made the construction of this home very complex. “We had to blast and cut the rock out,” explains Peter Campbell, whose company, Triple Star Management Construction and Building, built the house. But, the complexities were largely driven by the sheer weight of the roof structure, which belies the ballast roof’s slender profile and lightweight appearance. It had to be engineered to accommodate a considerable amount of gravel that is spread out over the entire roof, making the form seem more like part of the landscape from the air and looking down from the mountains.

At the top of the property, a natural tarn or small waterway filters down to a manmade reflection pond that sits below the house and, from certain angles, makes the building appear to float over water.

“The relationship of the house to the exterior areas was very important because the site can be prone to wind exposure, especially coming down the lake from Queenstown, but we’ve managed to create plenty of shelter from prevailing winds, seen in the central courtyard, terraces and a hot tub area that’s deliberately tucked away,” explains Francis.

“Essentially, in terms of the layout, the design brief was to create reception areas with visitors’ sleeping accommodation in a separate wing away from the buildings,” he adds. “It’s an ideal configuration for anyone living in this environment because it’s a real destination. We needed to make it easier for guests stay for longer periods than just one night, so the house feels more like a lodge.”

A two-storeyed wing faces the mountains to the east and a single-storeyed wing faces the lake to the west. “The west wing contains the main living spaces and a separate guest wing that can be closed off,” explains Hamish. “The upper level sits on top of the garage and has the master suite, a private lounge and two other bedrooms, each with its own private terrace, and each lounge follows the path of the sun.”

“The staircase is a really important piece in the design,” says Hamish. “Cantilevered off a silver travertine wall, it floats down from the timber floor of the upper level to the basalt of the lower level.” Here, a large kitchen, with a central island and a scullery, can be opened up to or closed off from the adjacent spaces, including the dining area, sunroom and outdoor terrace.

Throughout the home, a simple palette of materials responds to the natural environment. The main form of the house is clad in local schist from Alexandra, articulated with recessed windows, fascias and large overhanging soffits in powder-coated aluminium and selected areas of cedar cladding, which aid in reducing the visual mass of the stone walls. Inside, the floors flow from honed Timaru bluestone in the main kitchen and living areas to oak timber boards in the hallway and upstairs, and woollen carpets on the bedroom floors.

“The homeowner wanted a house that’s able to maintain 28–29 degrees in the winter because he spends a lot of time in Asia and likes a warm environment,” says Peter. However, given the extreme climate around Queenstown – which can range from very hot and dry with a lack of humidity in the summer to immense cold and snow in the winter months – a high-performing thermal envelope was necessary, with heavy insulation, airtightness and a warm roof – to help regulate the internal temperatures.

“When you have a lot of glazing, large voids and cold winters, you need some pretty modern, state-of-the-art heating systems,” suggests Peter. The house uses a ground-source heating system, which involved drilling eight bores 100m deep into the ground. “We’re taking the heat from the ground, boosting it with a heat pump, and using it to heat the internal environment, and we’ve also used one of those bores to draw water to feed the pond.”

Photo-voltaic solar panels have also been inserted on the building, positioned low from a visibility perspective, while maximising the sun to provide some electricity to the home, although it’s not completely off-grid.

“We’re seeing briefs become more about resilience and enduring architecture with consideration for sustainability and low energy,” says Hamish. “For larger houses in the landscape, they’re becoming quite specific to the specific characteristics of the site and, also, the clients’ lifestyles and how they will live in the property over time.

“When you are given such a special site – on top of a ridge with very few structures around – you’re effectively free to create the best possible response to the landscape,” suggests Francis. “It was exciting and extremely satisfying to be given such an extraordinary piece of land and such a special opportunity to design a project like this."

“We’re being reminded by our clients that New Zealand really is a world-class landscape and, also, a world-class lifestyle,” adds Hamish. “It’s becoming increasingly sought after and we enjoy the opportunity to design for these requirements.”

Words by Justine Harvey

Photography by ArchiPro and Simon Devitt – indicated as AP and SD.

See ArchiPro Project of the Month