Architecture & Design Jefa Greenaway

As technology features more heavily in our everyday lives, the value of authenticity and connection has never been greater. For Jefa Greenaway, Director of Greenaway Architects and Chair of Indigenous Architecture + Design Victoria (IADV), the key to achieving authenticity and connection in every project – whether residential, cultural or public – is an integrated design approach. We caught up with Jefa, amid his planning for next year’s Venice Biennale, to get his take on the role of integrated design in modern architecture.

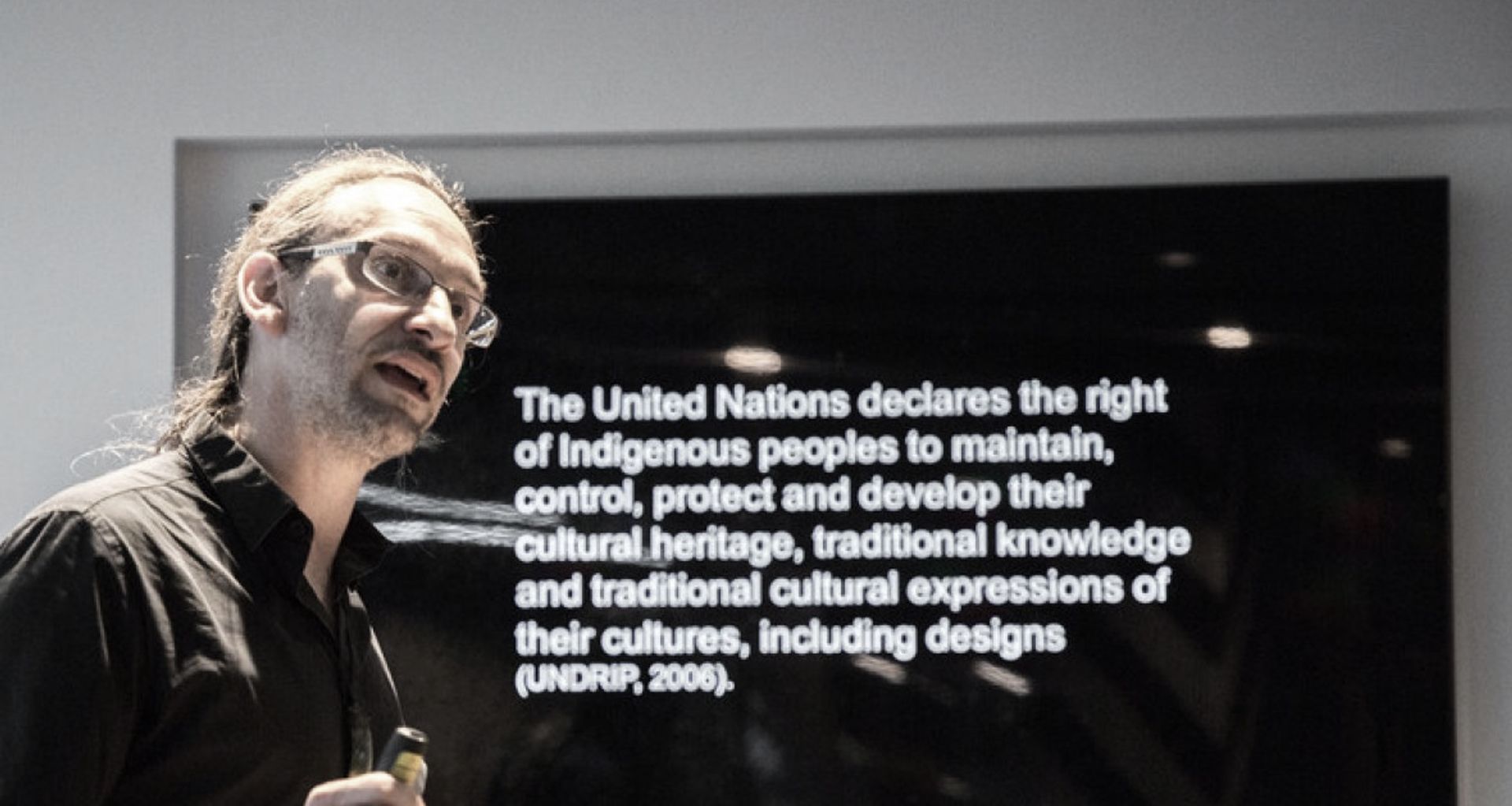

Jefa, as co-author of the Australian and International Indigenous Design Charters, a lecturer at the University of Melbourne and an ambassador for INDIGO (International Indigenous Design Alliance), it’s fair to say you’re one of Australia’s leading advocates for indigenous and integrated design. What is integrated design and why is it important?

In the past, there has been a tendency for different disciplines to be segmented on a design project. Integrated design is the process of taking a holistic approach and considering how we can create design that speaks to memory and history of place. It involves asking questions such as how do we make connections to country? How do we activate spaces? How do we develop opportunities for cultural narratives? How do we incorporate indigenous agency into our proposition? People are crying out for something that has meaning and depth. As we mediate a lot of our experiences through technology, the environment really enables us to connect to others – the places and spaces we create are an important factor in that connection.

What does an integrated design approach look like, at a project level?

It begins with a strategy that foregrounds indigenous voices. For example, on a current project, for the University of Melbourne’s Parkville Campus, we engaged with four traditional owner groups; this enabled us to hear the voices of elders and traditional custodians, their hopes and aspirations for the project. We can then look at how we incorporate those into a design proposition across a range of different domains – naming strategies, use of language, way-finding opportunities, art strategies, procurement policies to empower indigenous enterprise – a multifaceted approach.

The Parkville Campus is a signature project from the University of Melbourne’s reconciliation plan – can you tell us more about it?

Certainly – Parkville Campus is a large student precinct, covering a 2.5-hectare site. We’re collaborating with five other architectural practices and two landscape architectural practices, with the intention of stitching together an urban design, landscape and cultural narrative through a number of different buildings. It has huge cultural significance and raises the bar for integrated design processes. An important part of that is using local suppliers and, since the project involves a challenging topography, the need to manipulate drainage and waterflow, and water-sensitive urban design strategy, features many Stormtech products. In high traffic areas such as universities, it is essential to work with suppliers like Stormtech, who can provide high quality products that are fit for purpose.

Your relationship with Stormtech goes back a long way – can you tell us how it started?

I was a beneficiary of Stormtech’s scholarship to the Glen Murcutt International Masterclass in 2011. Within my cohort there were 33 participants across 25 different nations, so a very rich diversity of design practitioners across the globe. It’s an intensive experience, which went back to the basic principles of design, how we interrogate our processes and the essence of architecture – model-making, drawing with thick pens, pencils and charcoals. It was hugely transformative for me and an important reminder that it’s a privilege to create spaces that support and aid communities. The industry rarely recognises the importance of continuous learning and I commend Stormtech in their recognition of the value of education. As architects, while we may have spent many years at university, we can’t rest on our laurels and must keep honing our skills.

No-one could accuse you of resting on your laurels – on that note, how are the plans coming along for the 17th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale?

Very well, thank you. The International Architecture Exhibition happens every two years and is a vital opportunity to showcase Australian design on a global platform. Alongside my co-curator, Tristan Wong, our thematic is looking to challenge the notions of authenticity, how we can reveal our deep histories, interrogate ideas of representation and identity, and evoke connections to country. One of our objectives is to invite our neighbours, across Asia-Pacific, to discuss how we can meet the challenges of cultural integration that we’re all confronting, such as rising sea levels and the residual effects of colonisation. The Biennale is an exciting chance to share ideas, recognise the best and the brightest designers but, also, to celebrate our profession and the power of design to become an enabler.

As technology features more heavily in our everyday lives, the value of authenticity and connection has never been greater. For Jefa Greenaway, Director of Greenaway Architects and Chair of Indigenous Architecture + Design Victoria (IADV), the key to achieving authenticity and connection in every project – whether residential, cultural or public – is an integrated design approach. We caught up with Jefa, amid his planning for next year’s Venice Biennale, to get his take on the role of integrated design in modern architecture.

Jefa, as co-author of the Australian and International Indigenous Design Charters, a lecturer at the University of Melbourne and an ambassador for INDIGO (International Indigenous Design Alliance), it’s fair to say you’re one of Australia’s leading advocates for indigenous and integrated design. What is integrated design and why is it important?

In the past, there has been a tendency for different disciplines to be segmented on a design project. Integrated design is the process of taking a holistic approach and considering how we can create design that speaks to memory and history of place. It involves asking questions such as how do we make connections to country? How do we activate spaces? How do we develop opportunities for cultural narratives? How do we incorporate indigenous agency into our proposition? People are crying out for something that has meaning and depth. As we mediate a lot of our experiences through technology, the environment really enables us to connect to others – the places and spaces we create are an important factor in that connection.

What does an integrated design approach look like, at a project level?

It begins with a strategy that foregrounds indigenous voices. For example, on a current project, for the University of Melbourne’s Parkville Campus, we engaged with four traditional owner groups; this enabled us to hear the voices of elders and traditional custodians, their hopes and aspirations for the project. We can then look at how we incorporate those into a design proposition across a range of different domains – naming strategies, use of language, way-finding opportunities, art strategies, procurement policies to empower indigenous enterprise – a multifaceted approach.

The Parkville Campus is a signature project from the University of Melbourne’s reconciliation plan – can you tell us more about it?

Certainly – Parkville Campus is a large student precinct, covering a 2.5-hectare site. We’re collaborating with five other architectural practices and two landscape architectural practices, with the intention of stitching together an urban design, landscape and cultural narrative through a number of different buildings. It has huge cultural significance and raises the bar for integrated design processes. An important part of that is using local suppliers and, since the project involves a challenging topography, the need to manipulate drainage and waterflow, and water-sensitive urban design strategy, features many Stormtech products. In high traffic areas such as universities, it is essential to work with suppliers like Stormtech, who can provide high quality products that are fit for purpose.

Your relationship with Stormtech goes back a long way – can you tell us how it started?

I was a beneficiary of Stormtech’s scholarship to the Glen Murcutt International Masterclass in 2011. Within my cohort there were 33 participants across 25 different nations, so a very rich diversity of design practitioners across the globe. It’s an intensive experience, which went back to the basic principles of design, how we interrogate our processes and the essence of architecture – model-making, drawing with thick pens, pencils and charcoals. It was hugely transformative for me and an important reminder that it’s a privilege to create spaces that support and aid communities. The industry rarely recognises the importance of continuous learning and I commend Stormtech in their recognition of the value of education. As architects, while we may have spent many years at university, we can’t rest on our laurels and must keep honing our skills.

No-one could accuse you of resting on your laurels – on that note, how are the plans coming along for the 17th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale?

Very well, thank you. The International Architecture Exhibition happens every two years and is a vital opportunity to showcase Australian design on a global platform. Alongside my co-curator, Tristan Wong, our thematic is looking to challenge the notions of authenticity, how we can reveal our deep histories, interrogate ideas of representation and identity, and evoke connections to country. One of our objectives is to invite our neighbours, across Asia-Pacific, to discuss how we can meet the challenges of cultural integration that we’re all confronting, such as rising sea levels and the residual effects of colonisation. The Biennale is an exciting chance to share ideas, recognise the best and the brightest designers but, also, to celebrate our profession and the power of design to become an enabler.