Comfort in the time of Covid

Behavioural Designers take on the search for comfort in a time of discomfort and how to create visual comfort in our homes during a global pandemic. Very few things in history have caused as much disruption to our mental stability as Covid-19. It’s not so much the restrictions on travel that is playing havoc with our mental stability, it’s more the lack of not “knowing” what the future holds. Humans are hardwired to crave stability. Our brains don’t like uncertainty. We want to be able to predict with relative certainty what tomorrow will bring. This is also why technology develops at the speed that it does - or rather - why technology is presented at the speed it is. This is because humans can only accept a certain amount of change at a time, too much change makes us feel out of control.

What do a great idea and this pandemic have in common? We would say that they each suggest a great level of change. People are just not hardwired for it. This is also why ideas, even great ones, are overvalued. If a great idea requires a great change, then it will not be adopted. To a large extent, it is the same with COVID-19. In fact, this is mostly why we have so many conspiracy theorists. It’s a concept called proportional bias which holds that If the change is big, then the cause must surely also be big. This is to some extent why there are so many conspiracy theories around the death of Kennedy and so little around the attempted murder of Ronald Reagan. The difference is that the Reagan attempt had little consequence.

Emphasising the hardwired need for pattern and stability, in the face of a great change, means that we, therefore, need at least a great explanation that we can understand to bring us comfort. The truth is, we are probably never going to get this as in reality sometimes things just happen.

So, by extension, if we are hardwired for pattern and control, then in situations where a large part of our day is out of our control the only way to counter this is to make a much bigger focus on things that are within our control, according to just about every behavioural psychologist: We need to change the way we think.

A great example is the famous Psychiatrist Victor Frankl who survived the Nazi death camps by practising gratitude every day and went on to write a book about this, 'Man's search for meaning'. How he survived when all his family and friends perished. He mentions his daily search for anything to be grateful for from old memories to sunsets to being alive. So, the most powerful way to shift the focus is to practice gratitude for those things within our control however meagre they may seem.

“Victor Frankl survived the Nazi death camps by practising gratitude every day and went on to write a book about this, Man's search for meaning”.

So, without downplaying the suffering many people are experiencing or the seriousness of the situation, we can all stop to find all those moments around us.

Look what we have. We are online, chatting face to face, forming new meaningful human engagements like never before. It’s a difficult concept to grasp but luckily there is a lot of help available like The Smiling Mind app that can help to guide one to this method of thinking.

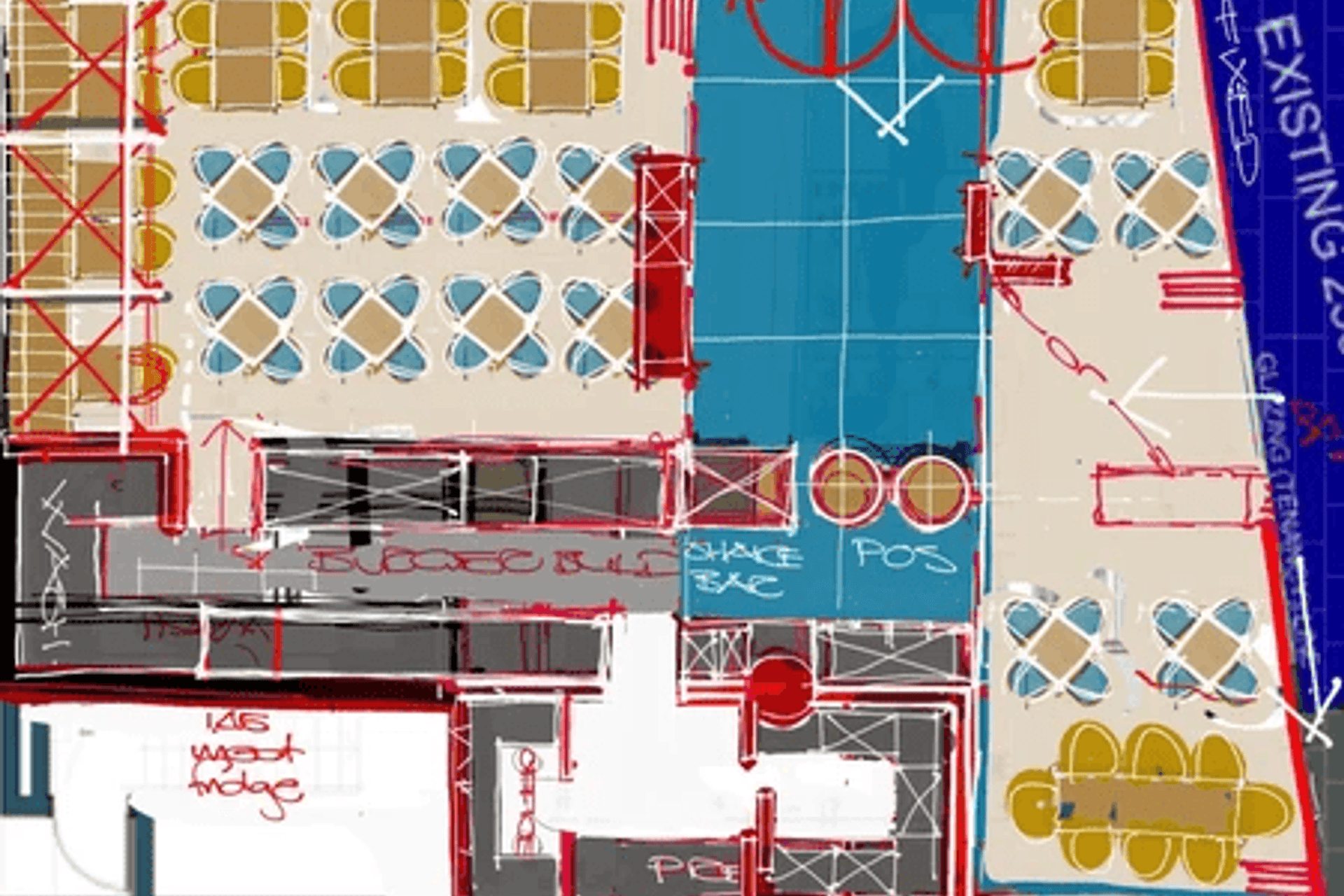

Creating visual comfort

Our homes have of course become much more important as places that can impact our levels of comfort and happiness. There are a few things we can do here with no money and immediate effect that will strongly impact our mental health. It’s a simple trick of taking stock of our room arrangements or furniture layouts and practice a simple trick referred to as Gestalt Psychology named after a very influential school of visual perception in Germany in the 1920s.

The notion is that our brains are hardwired to create order from chaos and in constantly looking for ways to frame everything, even visually. It wants to line things up. For example, It wants to see the corner of the couch lined up to the occasional chair on the other side of the coffee table. How many of us find ourselves down a social media wormhole of interior details that make our hair stand on end?

Johan Wageman is an experimental psychologist from Belgium who specializes in visual perception and how our brains constantly organize the incoming flow of information. He holds that symmetry is one of those major principles driving the self-organization of the brain. In short, our brain wants symmetry.

“You can also see symmetry as one of these major principles driving the self-organization of the brain.”

This is echoed by physicist Alan Lightman in his book ‘The accidental Universe: The world you thought you knew': "I would claim that symmetry represents order and we crave order in this strange universe we live in” One only needs to think about the petals of a flower, the wings of a butterfly, or even the symmetry in our outer body appearances to begin to understand the impact nature has on how we think visually. Symmetrical objects and images fit neatly into the patterns that our brains recognize as familiar.

The architecture of our brains was born from the same trial and error, the same energy principles, the same pure mathematics that happens in flower, jellyfish and Higgs particles,” writes Lightman

This is echoed by physicist Alan Lightman in his book ‘The accidental Universe: The world you thought you knew': "I would claim that symmetry represents order and we crave order in this strange universe we live in” One only needs to think about the petals of a flower, the wings of a butterfly, or even the symmetry in our outer body appearances to begin to understand the impact nature has on how we think visually. Symmetrical objects and images fit neatly into the patterns that our brains recognize as familiar.

The architecture of our brains was born from the same trial and error, the same energy principles, the same pure mathematics that happens in flower, jellyfish and Higgs particles,” writes Lightman

“The architecture of our brains was born from the same trial and error, that happens in flower and jellyfish.”

On the other hand, though, we easily bore from symmetry overload. Johan Wageman found that although our brains favour the order of symmetry, they are not necessarily more beautiful and this is where the Japenese concept of Fukinsei, creating balance in the composition or “counterweight” of dissimilar objects, comes into play. This has an equal bearing on art arrangement on a wall as it has in the way we layout spaces and the furniture within it. There is an “optimal level of stimulation” says Wagemans “Not too complex, not too simple, not too chaotic and not too orderly.”

Drink

On a more light-hearted note, there is also a very recent study and a book by Professor Edward Slingerland called 'Drunk' (released last month). One must not underrate alcohol and the rewards it triggers. He argues that there is a lot of misinformation about alcohol. It has helped man with stress reduction throughout the ages as captured in writings of the old Hebrew bible and early writings from Mesopotamia to China. In fact, he argues that alcohol also makes one much more creative. Studies have shown conclusively that a BAC of about 0.08 brings one to the most optimal creative ability.

“If you bring people to about 0.08 blood alcohol content, they do better at creative tasks”

Steve Balmer, the former CEO of Microsoft, discovered that his coding ability peaked at this narrow BAC and then declined immediately if he drank too much, so the narrative is that he kept himself on an IV drip of Vodka to stay in this bandwidth when he coded.

Whether the IV drip is a true or urban myth, it birthed the term “Balmer Peak”. This is known to be a sweet spot where we regain some of the creative cognitive flexibility we had as children. Sprinkle in a dash of gratitude to that cocktail and it may just bring us enough of that comfort we need in Covid.