David Ponting on shaping conceptual ideas into enduring architecture.

Written by

29 October 2025

•

4 min read

Every great building begins with an idea. Sometimes it’s as simple as a feather found on the sand. For architect David Ponting, the art lies in carrying that inspiration through the design process without losing its soul.

A home, however, must do more than embody an idea. It tells a story about the people who live there, the context that shapes it, and the land it inhabits. Yet creative vision must eventually answer to codes, budgets, timelines and the lives that will unfold within. As any architect knows, a concept is only as strong as its ability to serve the rituals and realities of everyday life.

Ponting Fitzgerald Architects’ David Ponting believes that the purity of an initial concept is essential for a design to resonate, yet knowing when to adapt is just as crucial.

“One of the hardest things to acknowledge is not when to stop, but knowing without a doubt you have gone far enough,” he says. “It’s important that the ‘pure’ idea has its time in the sun, but you must also know when to let it go.”

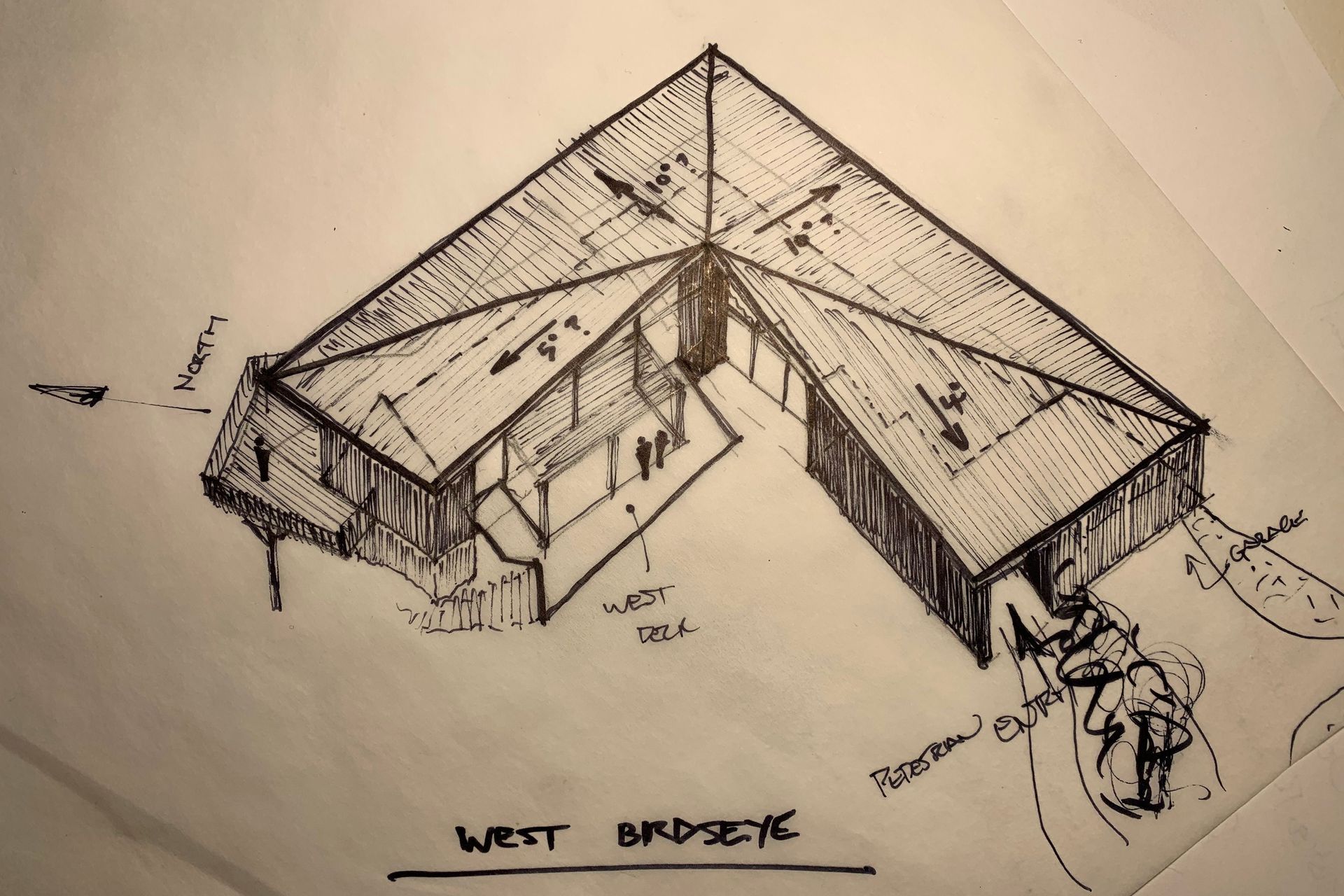

A recent project at the Tara Iti golf course in Mangawhai began with an unexpectedly poetic moment. The discovery of a feather on the beach.

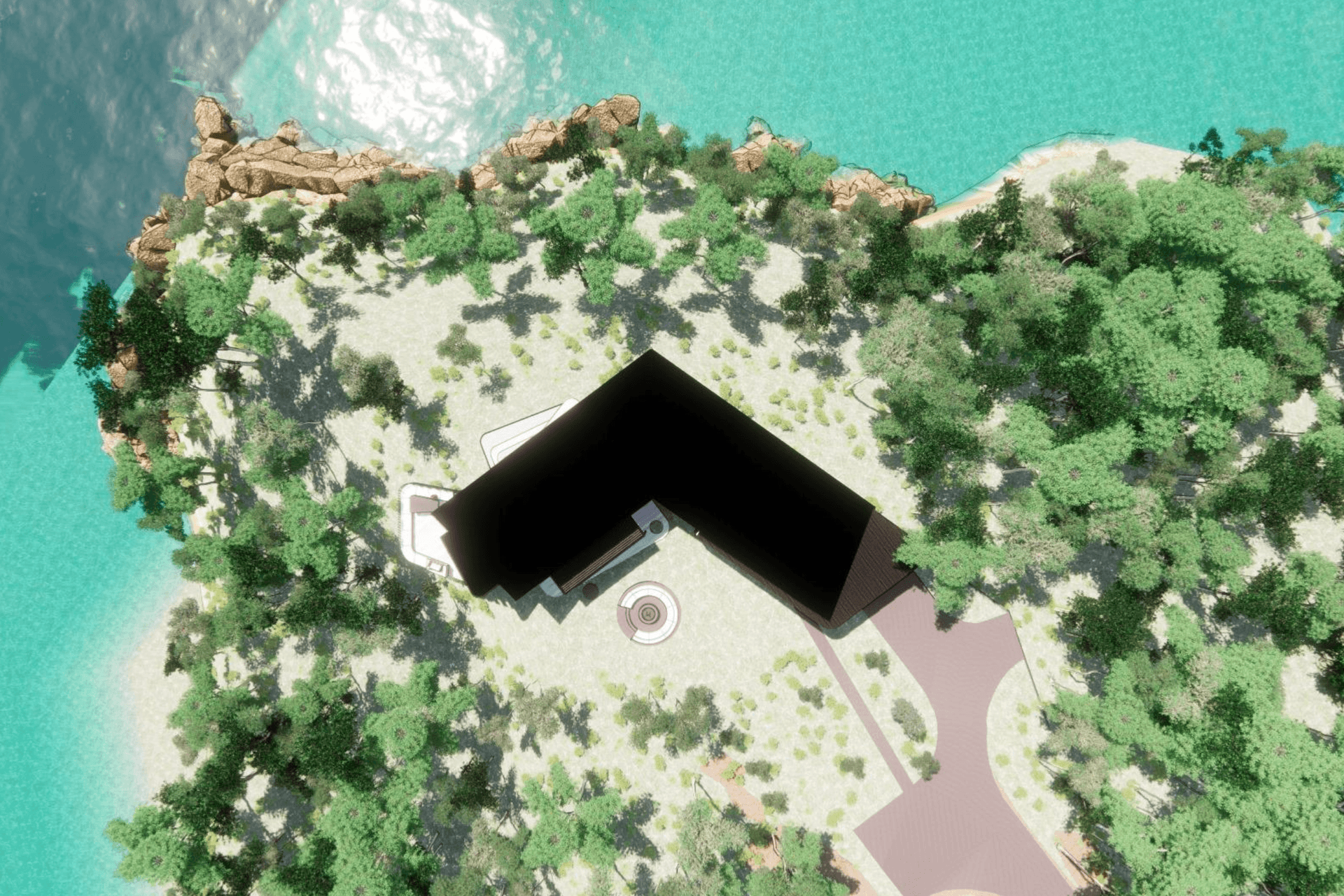

“We began this concept by observing the sand dunes and recognising when you go down to the shore you find things, such as a feather, a natural part of the landscape,” shares David. “Then playing with the principle of scale, we turned the feather resting on the sand into the origins of the roof form, expressing it as a sense of shelter to inhabit.”

The feather became the conceptual driver. An anchor that guided both the form and materiality of the home.

“It provides a story to then guide the ideas with consistency as opposed to making random decisions,” he says. “However, you can’t let the sculptural identity dominate and the practicality of the building be an afterthought.”

As the idea unfolds into built form, that conceptual clarity becomes a framework for every solution, from the layout to the way one moves through the home.

“I think the conceptual response and the narrative of the journey through the home happen in parallel,” shares David. “Resolving the spatial functionality, the arrival experience and prioritising this sequence of spaces relative to arrival, enhances the architectural experience from the car to the couch.”

For David, the process of design is both emotional and pragmatic. A continual calibration between poetry and practicality.

“On arrival, are you drawn through the architecture to the landscape it's sited within? When you design for emotional response, it's related to the architecture connecting with that landscape. It amplifies its better qualities and minimises the lesser, so when presenting our ideas, clients can imagine themselves getting everything from the experience of living there.”

Finding that balance is one of the most delicate parts of designing a home; it means recognising when an initial idea has reached its full expression. David likens the process to a set of scales, constantly tipping between art and utility.

“It’s like two things you’re balancing against each other,” he says. “Do you let the sculptural entity dominate, and have the practicality just sit as an afterthought? That can make a very beautiful building. Or do you shift it the other way and say every square metre must be hyper-functional, but increase the potential for an ugly result?”

When that balance is found, when an abstract idea becomes something you can inhabit, the story is enduring and so is the architecture.