One to watch: Danielle Koni

Written by

15 September 2021

•

6 min read

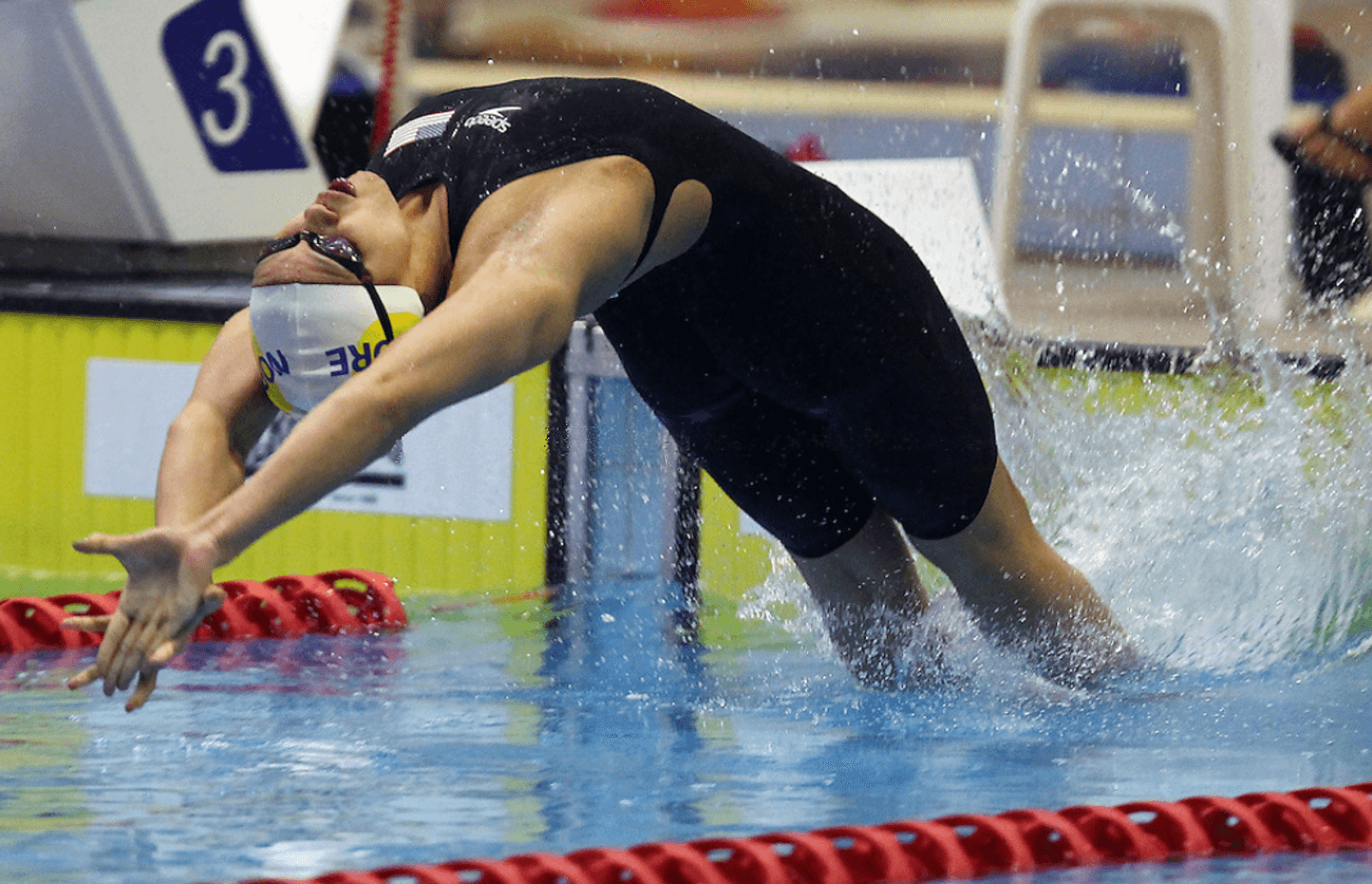

As a competitive swimmer in her teen years, Danielle Koni showed no inkling of an interest for the future career that would see her win architecture awards and become part of a movement to integrate Māori design principles into New Zealand architecture.

The ambitious and determined teenager moved with her parents to Brisbane when she was just 14 in pursuit of top level swimming coaching, where life revolved around the pool and homeschooling. But after three years of intense training and competition, Danielle was truly burnt out.

Drawing had always been a passion as a young child, so after returning home to New Zealand (where she continued to swim and compete), she put together a portfolio of artwork and took it into Elam School of Fine Arts.

Unfortunately, she discovered she’d missed the portfolio deadline, and was advised by her parents not to waste the portfolio she’d worked on. As luck would have it, Auckland University’s School of Architecture and Planning was still taking in applications, so Danielle applied and was accepted.

“I didn’t really know anything about architecture. I just knew I wanted to do something creative and that involved problem-solving.”

But having few expectations didn’t help Danielle in her first couple of years of the degree. She struggled to “get” architecture, and her time outside of school was still focused on swimming— she even competed at the 2011 World University Games in China.

But two things were to happen that would change the course of her career. First, she was injured at a training camp in Tahiti—an injury from which she never properly recovered, and second, she was introduced to her future mentor, renowned architect and professor Rewi Thompson.

“When he spoke about architecture from a te Ao Māori perspective—about the spirit of a place, the atmosphere, feeling, life and death, and environment—I clicked. That’s how I’ve been thinking about architecture ever since.”

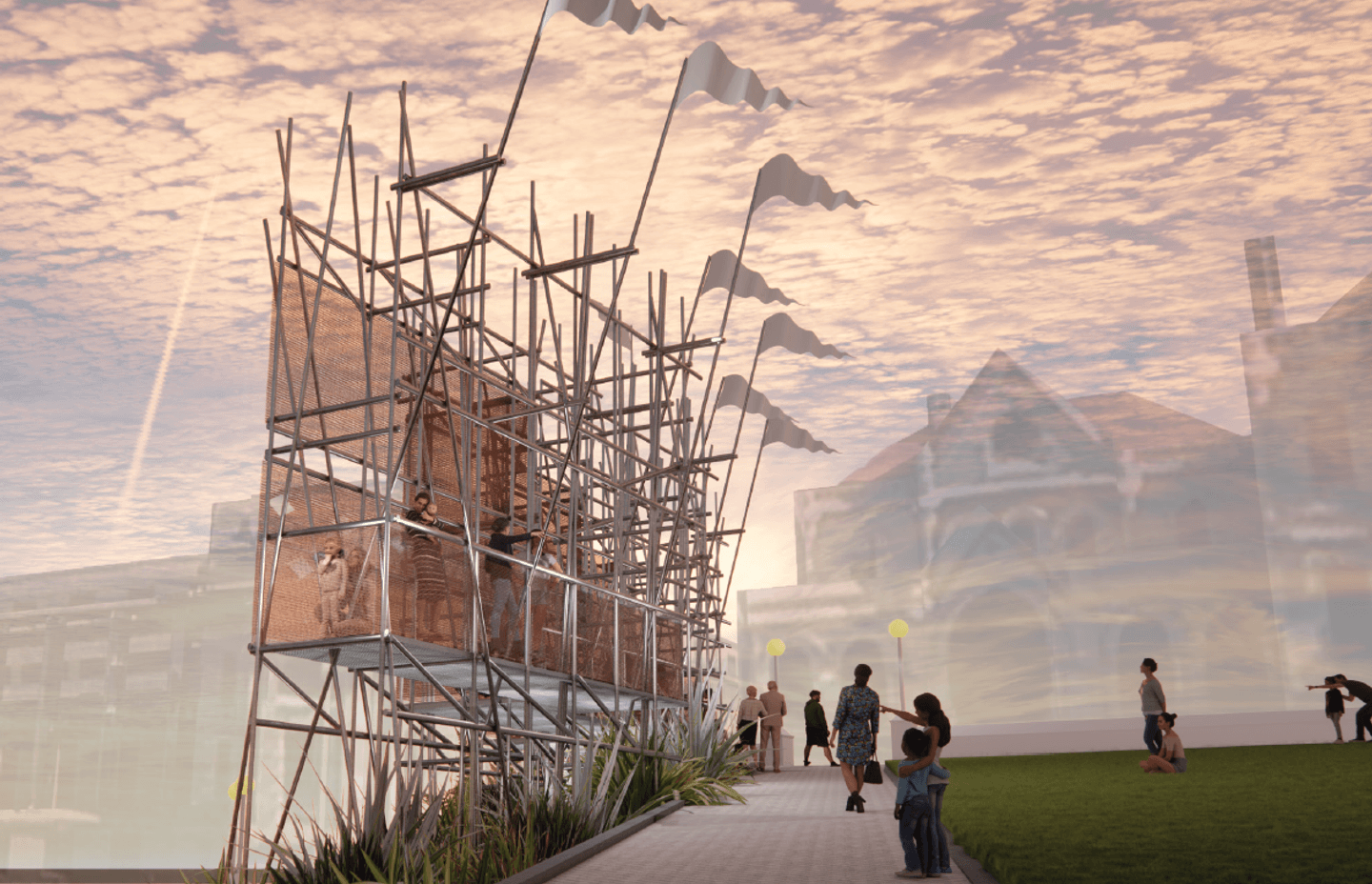

Danielle’s whakapapa is Ngāpuhi / Te Arawa / Ngāti Whakaue. Embracing her heritage and approaching her work from a Maori perspective changed her study of architecture entirely. She began doing well in her assignments and her final year thesis, which focused on the tensions between Ngāti Whakaue and Crown over the construction of a road through iwi-designated land (filtered through the figurative lens of weaving) received a Highly commended Student Design award from Te Kāhui Whaihanga New Zealand Institute of Architects.

It made perfect sense then, that following her study, Danielle was attracted to Jasmax, a firm that prioritises mana whenua in its work. There she joined Waka Māia – a collective within Jasmax of architects who specialise in engaging mana whenua, and applying te aranga Māori design principles to projects.

She’s now a Young Māori Design Leader within Waka Māia and says in her four+ years at Jasmax the adoption of a te ao Māori perspective in architecture has been increasingly embraced.

“[Waka Māia] were starting off by leading bi-cultural conversation within the office, educating internally as well as educating clients who were new to Māori principles, what that means for design and what it can mean for their outcomes and relationships with clients.”

She says in the short time she’s been there, the conversation has evolved.

“People are taking [Māori design principles] on board wholeheartedly and have started to engage with it earlier, which has always been our dream.”

Danielle works in a practice group that focuses on education, civic, culture and community architecture. She says clients are now seeing tangible benefits to adopting a te ao Māori approach.

“People often ask: what does a bi-cultural building look like? But I think we’re getting closer to the conversation where it’s not just about what it looks like, but how the building is used, the end use, the length of the life, and the sustainability strategies.”

She’s led the cultural conversation for designs at Western Springs College and the University of Auckland’s B201 Building (in collaboration with Karl Johnstone and Joe Pihema from Haumi) and she says post-occupancy studies are creating evidence bi-cultural design.

“At university we’re looking at an increase in enrolment for Māori and Pacific; there’s lots of social benefits and we’re just starting to get some quantifiable evidence. Before it was qualitative and that was quite hard to explain!”

Danielle says that tapping into indigenous knowledge means tapping into the relationship between tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti and forming a holistic view that integrates easily with sustainable ethos.

“It’s not like you have a sustainability strategy and you have a Māori design principles strategy, because there are just so many overlaps… infusing those ideas into a building is really meaningful and beneficial to everybody.”

Since working at Jasmax she’s collected many more mentors who’ve had a positive influence on her work. She lists Elisapeta Heta (Maori design leader at Jasmax), Sarah Treadwell and famed Māori artist Maureen Lander as big influences.

Alongside Maureen Lander and Sarah Treadwell, she recently participated in creating a proposal for a sculpture for the Wellington parliament grounds that celebrated the New Zealand’s Women’s Suffrage movement. She was thoroughly inspired by the collaboration, which delved into Māori mythology to celebrate women’s strength, but laughs that their sculpture wasn’t selected because “it wasn’t submissive enough!”

She’s currently involved in the design of a marae at North Shore Hospital's campus, was recently promoted to an Associate, and plans to become a registered architect. She says it’s important for the younger grads to see Māori represented in senior roles. On this note, she has some personal goals that will help her become the kind of mentor that she herself has taken strength from.

“I want to become better at speaking because I think that I can’t lift people up if I can’t talk to them about what it’s going to take, and how the journey might look.”

She says taking on the role of mentor and helping guide younger people in the industry is a key goal, but that her ability to speak in public is “probably my biggest weakness”.

Unsurprisingly, the determined architectural graduate plans to change that.

“I’m kind of weird like that— I want to have a go at my biggest weakness and I just go really hard at that because I always think if I just work really hard it could become one of my strengths!”

Banner image: Danielle in front of her award-winning thesis project.

Image courtesy of David St George, Te Kāhui Whaihanga New Zealand Institute of Architects