Tailored Models

Around the world, major cities are facing housing crises as populations shift to predominantly city-based lifestyles – pandemics notwithstanding – and as housing prices have been rising unsustainably in many cities. Housing delivery, however, is still falling further and further behind demand, resulting in a lack of affordable residential stock and a lack of choice for homeowners.

‘Mass Housing’ (any development which includes 150+ units) is a product that is now facing several conflicting challenges. This is made even more complex by the fact that developers are not just providing what is often the largest purchase in people’s lives, which forms a huge part of people’s self-identity but are also attempting to deliver at scale with immense cost pressures.

Today, private developers are necessarily driven to generate profit, while delivering homes that will meet the relevant regulations. To deliver profit and housing at scale, private developers create highly repeatable and space-efficient homes, that can be built profitably at market values.

Looking globally, we also find that residential is one of the most regulated sectors, particularly in terms of space standards and requirements. While these regulations and requirements vary dramatically by country, region, city, even borough, it is understood that homes should meet minimum levels of quality to ensure the safety, health, and security of a city’s residents. Combining strict local regulations to housing, with a reliance on private developers to deliver, leads to mass housing being one of the most homogenous sectors in property. This leaves limited choice for most people, as the market eventually establishes the most efficient way to deliver housing that complies and then repeats it.

Equally, the risk of failing to attract residents leads most developers to typically take the efficiency of a highly repeatable product that does not offend anyone, rather than targeting the tastes and desires of a specific audience.

So, how does a developer create a home that is personal, while still appealing to the widest possible market?

We believe there can be a different approach to mass housing which would offer developers an efficiency of scale and provide homeowners some flexibility and choice before the point of purchase. Our “Choreography of Selling” approach to residential design focussed on understanding the target market for each project, creating specific designs that support the lifestyles, ambitions, and aspirations of that market. While successful, this required bespoke designs for each project, with little repetition between them.

So how do you offer a home which feels like it has been specially designed for its resident, without bespoke designing and building every part? Housing, as a ‘product’, shares these factors with cars – another significant purchase, that reflects on people’s sense of self, while being made at scale every year. The auto-industry has addressed this by engineering chassis platforms which support a whole range of models, each of which then has a suite of options which can be tailored by the customer.

The Mass Housing Platform Approach

With the construction industry facing labour and talent challenges (as outlined the 2016 Farmer Review) and with mounting pressure on cities, markets and developers to make up the housing supply shortfalls, we are seeing the streamlining of the mass housing development process being taken seriously by many of our residential clients. Creating design frameworks which solve the mundane and repetitive elements of the development process allows developers, designers, and constructors to focus on unique and differentiating elements of each project. The intent of which is to reduce time spent reinventing the wheel and more time on adding value to a project, whether financial, experiential, community, design quality or other types of value.

We suggest taking this concept further, taking Mark Farmer’s advice to heart. Learning from industries which have successfully modernised, the automotive industry analogy above could be applied to mass housing development.

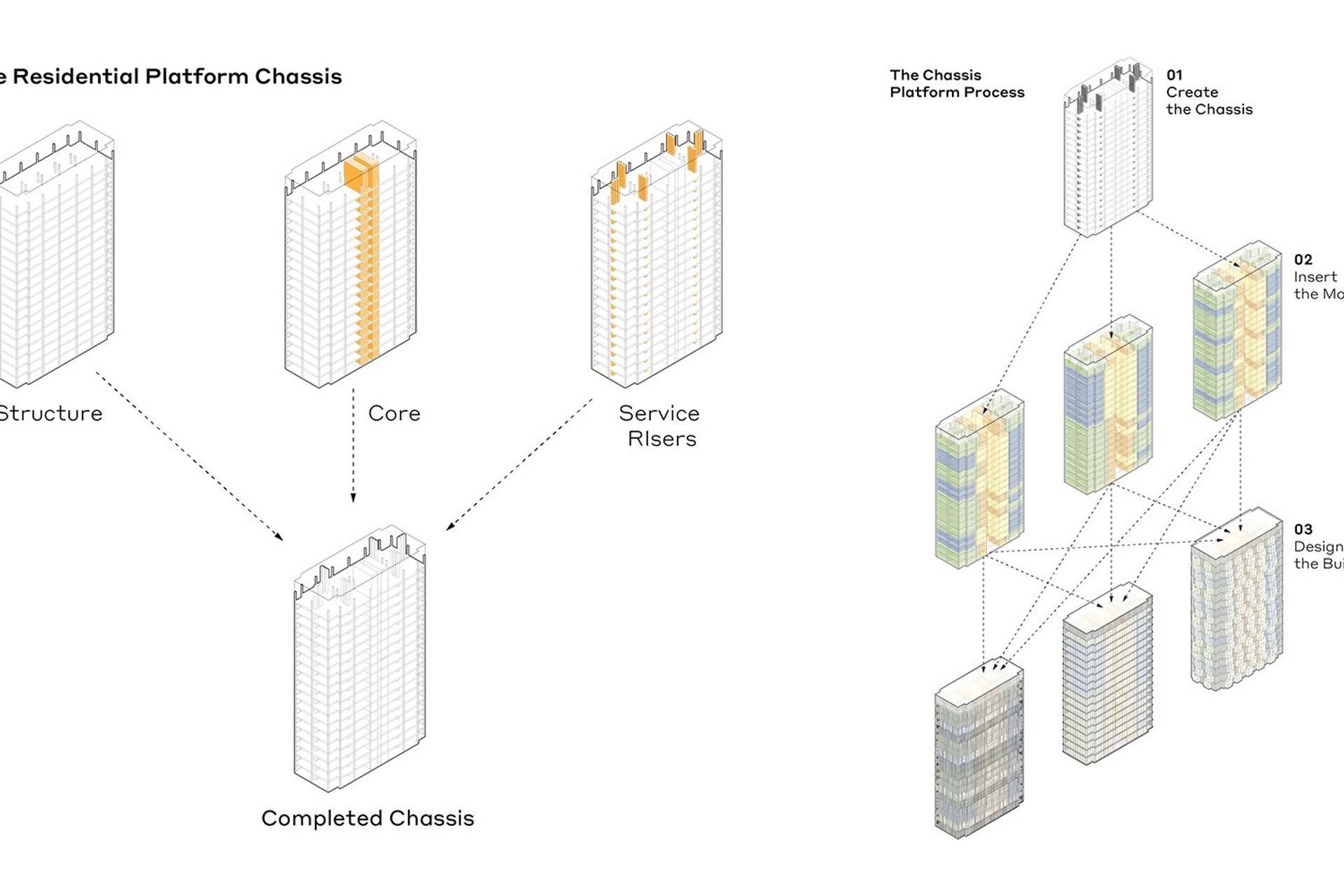

Chassis Platform / Construction Methodology

Automotive groups spend enormous amounts of effort and resources to develop their basic chassis platforms, which underpin their model ranges. Auto-manufacturers may then have multiple platforms (or variants of these platforms) to suit the models or segments that are not suitable for a single platform solution.

Mass housing developers can take a similar approach, developing a platform that underpins their range of projects. This platform could be based on construction methodology (traditional construction, modular component construction or full volumetric) or structural solution (steel, concrete, composite, CLT etc.) or a combination of the two. These can then be designed for maximum efficiency, identifying key spans, dimensions, grids and so forth that suit the platform, with parameters that can be applied to projects consistently.

Establishing the parameters for the underlying platform of mass housing developments allows developers, designers, and constructors to understand and establish these critical decisions before the design progresses. It must however be developed with the ultimate outcome in mind, the platform must support the creation and delivery of high-quality housing that meets all the various requirements placed on it.

Such an approach, if applied to the housing industry, could have multiple implications, not least on the sustainability of the housing industry. While fulfilling the demand for affordable housing in many urban centres, it would also allow us to create developments that ultimately last longer and are easier to adapt internally, rather than demolishing and re-building each time. People would have the opportunity to live in a place and build a community that lasts for the long term.

There is also the economic factor to consider and a likely cost increase due to new construction complications – but this is something that will be offset by differentiation and speed of sale. Subsequently, once you get to a certain scale, the cost will be offset by volume.

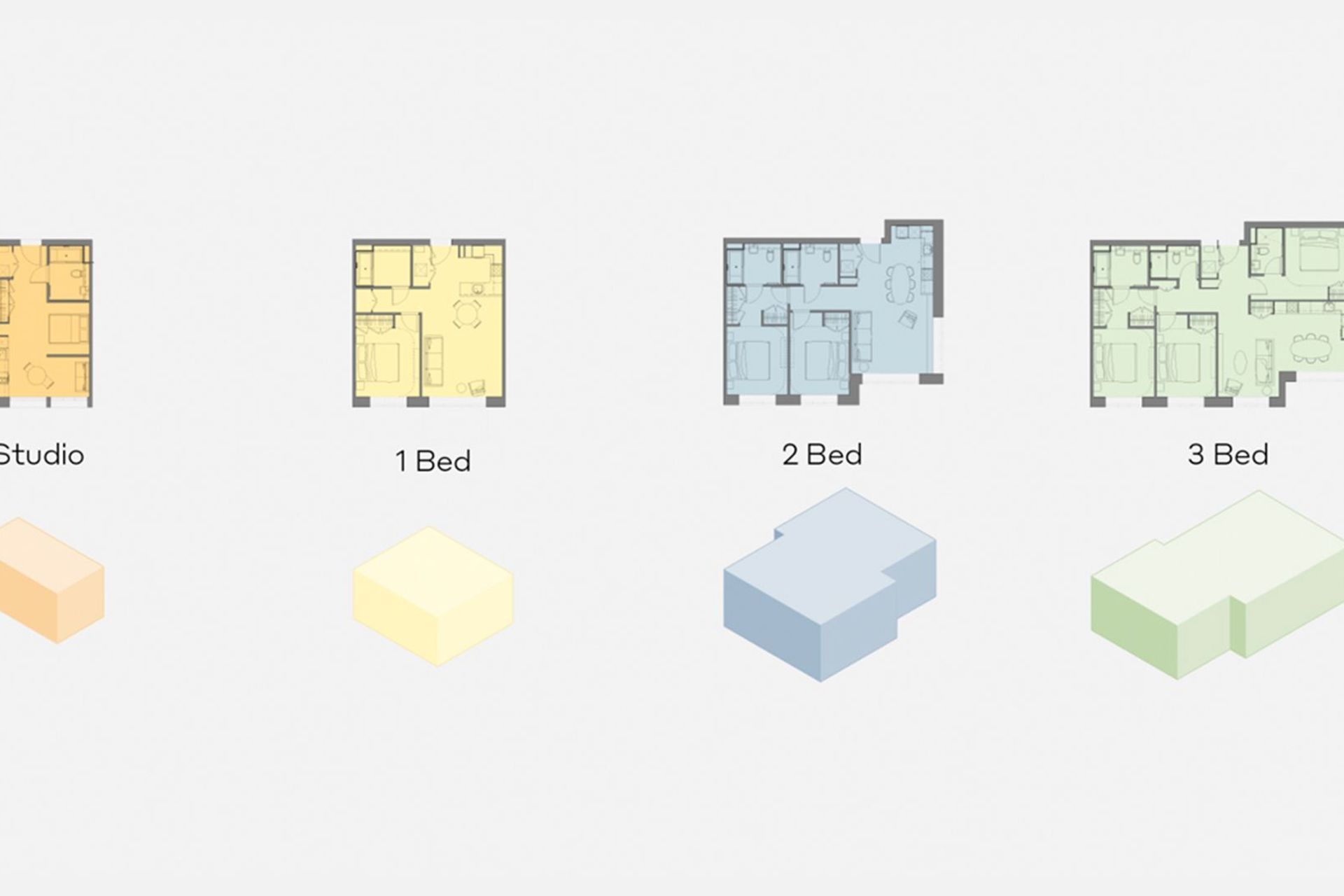

Residential Models / Typologies

Mass housing tends to take the form of a range of apartment typologies, studios, 1-bed, 2-bed or 3-bed homes. These can be considered analogous to automotive segments, from studio or city car through to 3-bed or SUV comparisons. These segments then break down even further into various models, which offer further variants to suit more specific tastes and other factors.

Just as people need different sized cars, they also need different sized homes depending on their own circumstances. These typologies are already well understood in the market and the standardising of these forms the basis of many developer’s design frameworks. These typologies tend to set the location of key services coordinated with the platform for efficiency.

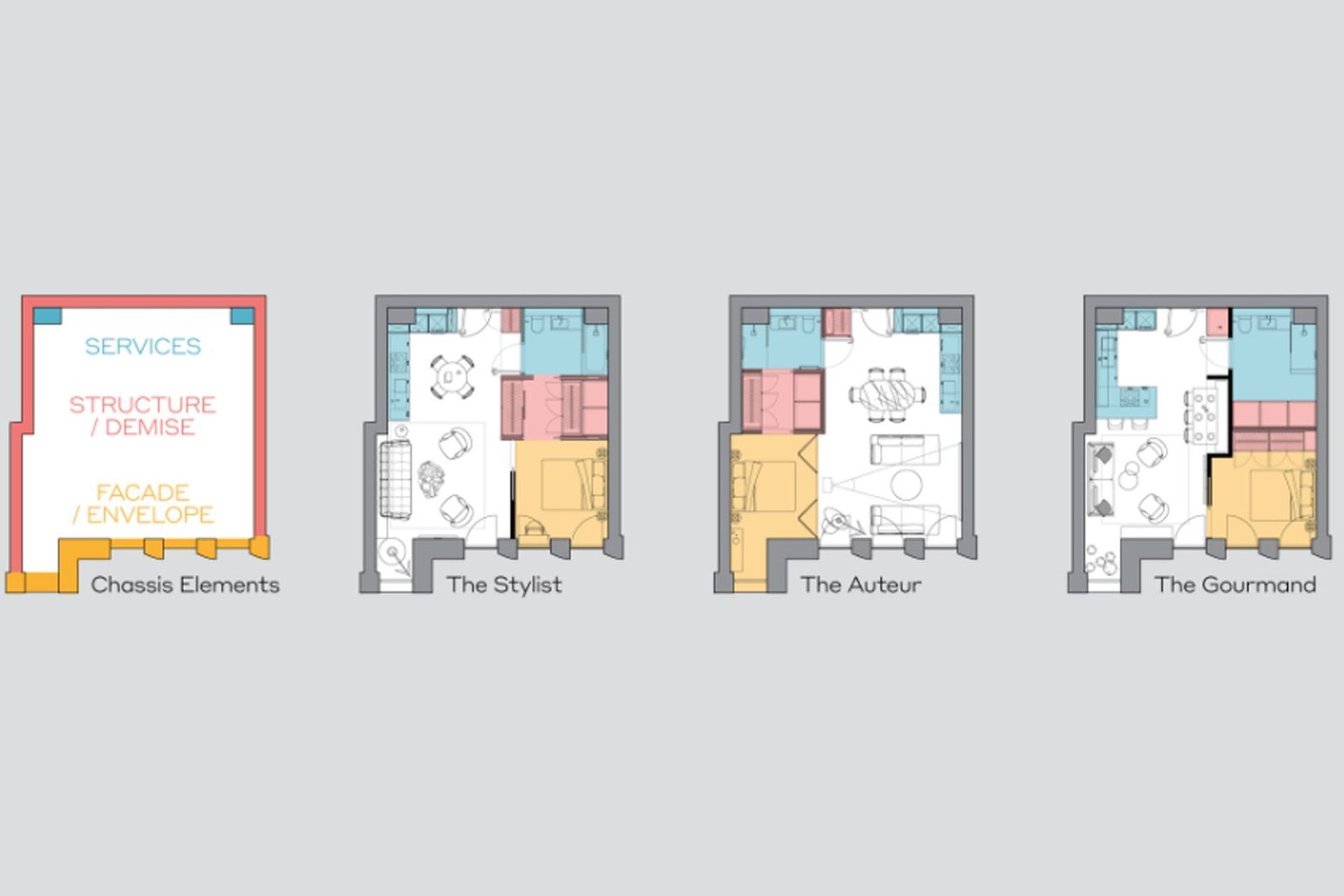

Lifestyle Layouts / Other Options

The failure we see in the current housing market is the homogeneity of the housing once you get past the typology stage, apart from a few variants such as the “dumbbell 2-bed”, there are relatively few arrangements for modern mass housing, driven by the need to deliver a space as efficiently as possible within the applicable regulations. We understand that the process outlined above would provide end-users with more options, while still simplifying the customization process for private developers.

By fixing in place all the “hard stuff” such as structure, service risers and connections, fire breaks and demise walls, apartment layouts can be more flexible to support individual purchaser’s lifestyles. After the hard stuff, everything else is plasterboard partitions and joinery, which should be more readily suited to each resident’s lifestyle.

Woods Bagot have been exploring this approach for years. Our project in Melbourne Australia, the Sunday Apartments (above), took this approach to the extreme by only building demise walls between the apartments, with the rest of the fit-out being part of a large, single joinery element. This joinery element included the kitchen, bathroom, wardrobes and storage, while also dividing the space within the apartment into rooms. As a joinery element, the fit-out could then accommodate client alterations without impacting construction works.

Say you are an avid cook and you love to entertain and feed your friends, you should be able to prioritise your kitchen and dining space, compromising your living area or bedroom. Or you might be an ambitious professional who works all hours, eats at business dinners and is only home for sleeping and bathing. Shrink the kitchen and enjoy a luxurious bedroom and bathroom master suite that suits your lifestyle. These personalities and the layouts which appeal to them can be established as options within a platform approach, pre-designed and ready to fit seamlessly into the platform alongside the standard models.

Conclusion

There are of course realities and challenges to this vision of tailored mass housing; options add cost and complication to construction. Offering options works for pre-sales, but how do you manage them for a BTR scheme? Every project is different, but only offering the options for pre-sales and then including a proportion of options in the construction may solve both problems. In BTR market research might offer an insight into the market interest in different options that can be offered.

If done correctly, this approach can offer the best of both worlds; it widens the market you can appeal to by offering more than the standard homes in the market, while also providing a more personalised home that residents can identify with. Residents will feel they have had far more influence on the layout of their home, tailored to their specific needs at a more affordable price point.

We often talk about what the new high-quality defining factor might be in housing as society evolves and reacts to new ways of living and working. Whereas before it might have been access to an outside space such as a balcony, or having a gym in your development, perhaps now it can be just the simple, yet effective, ability to tailor your own space.