The Celata 88 Story

Ultimately, the form was dictated by function. The only non-functional structural features of the Celata 88 are the two chamfers on the top edges—they just look better than sharp corners. Even so, the cabinet design is reminiscent of Onken speakers, a Japanese design from the 1960s and 70s, but with large front chamfers to reduce edge diffractions for the mid-bass, which produces cleaner sound and better imaging. The slots of the Celata subwoofer design, the bottom two slots and the top two front-facing bass reflex ports are, of course, functional, and allow the speakers to be placed directly against walls.

Dynamic Waveguide

The biradial approach to the Dynamic Waveguide was inspired by the horns of Japanese designer Yuichi Arai, but with profiles optimised by modern computer simulations, and with large roundovers to prevent edge diffraction. In what is probably a first for the industry, we combined two incompatible theories to design the waveguide profiles: traditional horn theory, which dates to the early 1900s if not the late 1800s; and modern waveguide theory, which was first published by Dr Earl Geddes in 1989 and has advanced considerably since.

The primary goal of a horn is to acoustically couple the driver with air, with directivity control a secondary consideration. Waveguides are the opposite and are made possible by more efficient drivers—they control directivity as their priority, minimising what Geddes called Higher Order Modes that contribute to the honky characteristic of horns. In early listening tests we liked the dynamics of horns, a result of good acoustic coupling with air, and the intimacy of vocals that direct radiating tweeters simply cannot match. But we also liked the transparency and constant directivity of waveguides based on Geddes’ oblate spheroid profile. So, we tried using a traditional hypex profile vertically with a horizontal oblate spheroid profile and they worked brilliantly together: the dynamics of a horn without the honk and the transparency and constant directivity of a waveguide horizontally where it matters most. The 90-degree constant directivity horizontally assures that reflections off walls have the same frequency distribution of direct radiating sound; the narrow vertical dispersion minimises floor and ceiling reflections. Both help the Celata 88s sound great even in highly resonant rooms without acoustic treatment.

For the compression driver on the Dynamic Waveguide we realised early on that we didn’t like titanium diaphragm drivers, including coated titanium, because of their fatiguing sound. We quite liked an aluminium diaphragm driver but one failed during testing. We landed on an oversized ketone polymer diaphragm driver because of its smooth yet detailed sound that is not at all fatiguing. Being oversized, the diaphragm has to travel less in the voice coil gap than typical 1-inch compression drivers and, as a result, intermodulation distortion is reduced. Further, it has a 110 dB per W efficiency with a maximum power handling rating of 140 W, which it will never see in the Celata 88 because it is highly attenuated to match up to the mid-bass. As a result, the diaphragm hardly has to move to produce very high sound levels and it has far more overhead than a direct radiating tweeter, many of which would show signs of power compression and distortion at the SPL the Celata 88 can produce.

The Celata subwoofer design was a result of trying many woofer configurations, including things like transmission lines, in listening tests. In those tests slot-loaded woofers sounded better than direct-radiating woofers, two woofers facing each other into a shared slot sounded better than a single woofer through a slot, and two woofers back-to-front sounded better than that. We didn’t invent the push-pull configuration, but it is unusual, possibly a first, to have both woofers front facing, which is what we did to fit them into a narrow, compact cabinet. The front woofer fires into a channel that loops back into the main cabinet. Structurally, the front facing design works well because it produces a very stiff cabinet without additional bracing, especially when made from 18 mm plywood and combined with the bass reflex ports above the subwoofers. Sonically, the benefit of push-pull subwoofers is that even order harmonic distortion cancels out, which is the commonly cited reason push-pull woofers sound good. However, we believe an additional reason for their superior sound compared to direct radiating woofers is that two cones working in opposition provide a sort of negative feedback that reduces overshoot and ringing. In other words, they produce crisp, clean bass that is well matched to the mid-bass.

Another benefit of the dual subwoofers in a chamber that fire through two ports is that they form a 6th order bandpass configuration, which is often used in pro audio, but not in HiFi. In pro audio 6th order bandpass subs are popular because they increase gain by a few dB. They’re not popular in HiFi because the higher of the two resonant frequencies, the frequency associated with the smaller chamber, introduces undesirable group delay. We circumvent that problem, but still benefit from ~2 dB gain, by crossing over the subwoofers to the mid-bass well below the resonant frequency of the subwoofer chamber. We begin the sharp low pass filter roll-off about two octaves below the resonant frequency, which is difficult to achieve in a passive crossover but worth it. Additionally, we notch filter the resonant frequency of the subwoofer chamber to prevent any chance of it interfering with the mid-bass.

Mid-bass

The graphene-coated, magnesium cone mid-bass was selected from 9 months of listening tests of ~20 mid-bass and mid-range drivers. Its powerful motor is loaded with copper shorting rings, which reduce its intermodulation distortion levels to nearly the lowest theoretically possible from the Doppler effect. The driver can produce much lower frequencies than it does in the Celata 88, but, by not going as low as possible with it, its excursion is minimal, thus substantially reducing the Doppler effect on intermodulation distortion. Its copper phase plug, in combination with a titanium voice coil former, provide excellent cooling that makes it possible to drive at high levels for extended times without thermal power compression.

In our listening tests we didn’t like the colouration that paper cones create, especially with vocals at high levels, and polymer cones lacked the punch of magnesium. Magnesium is an excellent cone material because it is lightweight and rigid—the mid-bass is pistonic through its entire range in the Celata 88—and it is self-damping, which means it adds virtually no colouration to the sound. We can’t say what sonic effect the graphene coating might make because we didn’t compare it to other coatings, but at the very least it is an excellent material for preventing corrosion of the underlying magnesium.

The mid-bass is housed in its own densely packed, highly damped sealed chamber so that it is critically damped (Q = 0.5). Critically damped means that the cone doesn’t overshoot or ring after a signal has passed, much like the Celata subwoofers. Also, the densely stuffed chamber absorbs sound from the back of the cone so that it doesn’t radiate back through the cone to the listener. In listening trials we liked the clean and transparent sound of open baffle speakers, which is presumably from the lack of sound reflecting from an enclosure back through the cone. So we tried stuffing enclosures more and more with fibreglass and recycled fabric until the point where the sound opened up like open baffle speakers and that’s what we went with for the Celata 88. The result is lifelike instruments and engaging, intimate vocals.

Crossover

The crossover is the result of 11 months of listening tests to optimise component selection and filter topology. We even listened to the effects of different types of hookup wire and binding posts. During much of the Celata 88 development we used digital signal processing (DSP) to digitally create crossovers, so we had a good idea of what we wanted out of a crossover, but building a good passive crossover is much more complex than simply recreating DSP filters passively. Notably, in our experience, a relatively simple crossover that reproduced the DSP filters sounded worse than the DSP version. The challenge was to optimise the passive crossover so that it sounded better than DSP and, in fact, sounded like it wasn’t there at all.

The distinguishing features of the resulting crossover, which does sound better than DSP, are that its capacitors are all DC biased by 18 V and the topology of the 1300 Hz point is quasi-transient perfect. We didn’t invent either but came to use them through listening tests. JBL patented the DC bias approach (now out of patent) and still uses it in very high-end speakers. For the Celata 88, DC is provided by two 9 V batteries per speaker that are accessible on the back panel without tools. DC biasing capacitors draws virtually no current, so the batteries will not run out. They should be changed at the end of their shelf life, which is usually 5 years for alkaline batteries, 10 years for lithium batteries. We ship Celata 88s with alkaline batteries.

DC biasing the capacitors improves sound quality by effectively shifting the audio signal as it goes through capacitors so that, for most signals at reasonable listening levels, the capacitors never cross their 0 V point at which they are non-linear and distortion can occur. The downside to DC biasing is that it is done by doubling the number of capacitors and increasing their capacitance 2-fold because each pair is in series, both of which add complexity and expense, but it’s worth it. Additionally, we use bypass capacitors because they improved sound quality even in circuit positions where we didn’t think they would. As a result, there are 42 capacitors in the entire crossover per speaker.

All the capacitors for the Dynamic Waveguide are foil and film, including four custom made copper foil ones. The mid-bass capacitors are all metallised polypropylene (MKP) bypassed mostly with custom aluminium foil and film caps, including MKP capacitors of very high values because of the low 130 Hz crossover point with the subwoofers. The subwoofer capacitors are electrolytics bypassed with MKP caps. We used electrolytic capacitors with the subwoofers because, in total, the subwoofer capacitor requirement is over 3500 uF—MKP caps totalling 3500 uF simply wouldn’t fit inside the cabinet. The crossover, split over three boards, barely fits in the cabinet as is.

Swiss acoustic engineer Samuel Harsch first described his quasi-transient perfect topology in 2008. It time aligns the Dynamic Waveguide with the mid-bass by using asymmetric filters and by placing the acoustic centre of the Dynamic Waveguide ½ the wavelength at the crossover point, 1300 Hz, behind the acoustic centre of the mid-bass. The mid-bass is rolled off more steeply than the Dynamic Waveguide, which results in greater group delay than the Dynamic Waveguide filter (all filters add group delay). The ½ wavelength physical offset makes up the difference in group delay between the two asymmetric filters so that the Dynamic Waveguide and mid-bass are perfectly time aligned, as opposed to the vast majority of tweeter-mid-bass combinations in which the mid-bass lags the tweeter in time. The result is coherent sound through the crossover point, crisp transients, and true-to-life timbre, especially for percussion and plucked instruments. Surprisingly, even instruments that play fundamental notes many octaves below the 1300 Hz crossover point, such as kick drums and double bass, benefit from the time alignment because their harmonics extend into the range of the Dynamic Waveguide. Sonic coherence of the subwoofers, mid-bass, and Dynamic Waveguide is also aided by the rapid burst decay of each—each is down >30 dB by five cycles or less, which is a very fast and uniform burst decay across a 3-way speaker.

Materials and Construction

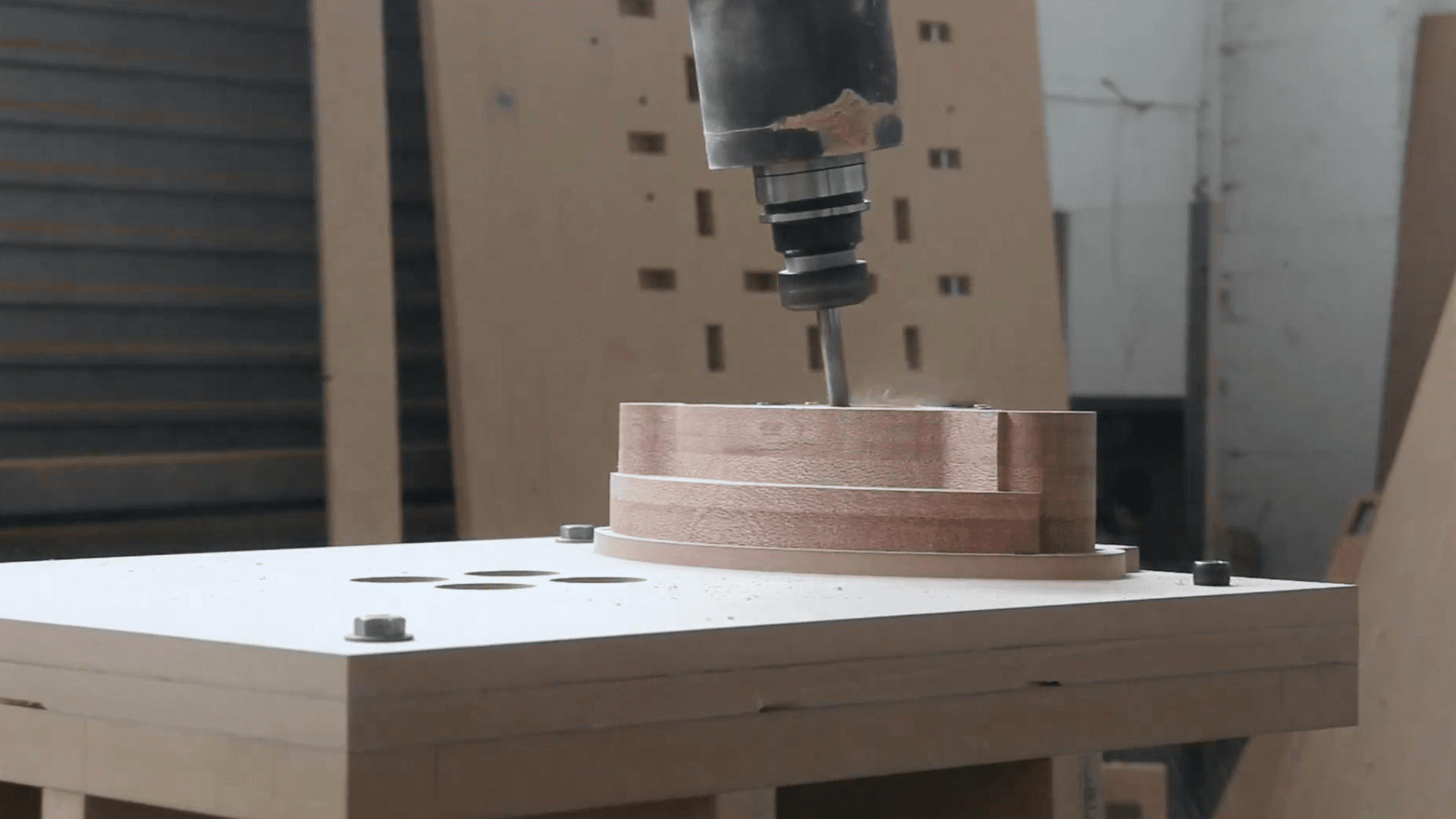

We use only responsibly sourced Australian timber that is processed in Australia. Our cabinets are hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamii), which is native to Queensland. The hoop pine we use is plantation grown in Queensland and is processed into plywood in Brisbane. Our Dynamic Waveguides are made from either laminated hoop pine plywood or specialty timber such as plantation grown Northern silky oak (Cardwellia sublimis) or salvaged timber such as the red ironbark (Eucalyptus sideroxylon) currently available in our Limited range.

Our cabinet panels and interior pieces are cut using CNC and assembled in Preston, Victoria, just outside Melbourne. Dynamic Waveguides are milled on a 7-axis CNC robot in Preston, also. Crossover and final assembly takes place in Inverleigh, Victoria.