Sited just a stone’s throw from Wellington city, this ‘hybrid city-country house’ has been designed to mitigate strong winds and blend into its rugged hillside setting.

High on a wild and windy hill above Wellington is an unusual site that was once home to three ostriches, leading, of course, to its name, Ostrich House. While two of these birds have sadly passed on, due to old age, the last one still roams the area and frequently saunters up to the fence to greet Brooklyn’s constant supply of visitors who roll in on their cycles to tackle its rugged hillside trails.

Due to its strong winds, in 1993, Brooklyn was chosen to be the home of the first power-generated windmill in New Zealand and, today, it continues to feed power into Wellington’s network – to power about 400 homes. So, it’s hardly surprising that Wellington-based practice Parsonson Architects responded to this location with a house design that helps to mitigate the wind.

“This site is even windier than in Wellington,” explains architect Gerald Parsonson. “Under the New Zealand Building Code, it is regarded as a place with ‘special climatic conditions’ because of the wind speed, which predominantly blows in from the north/north-west, and is increased due to being at a higher altitude.”

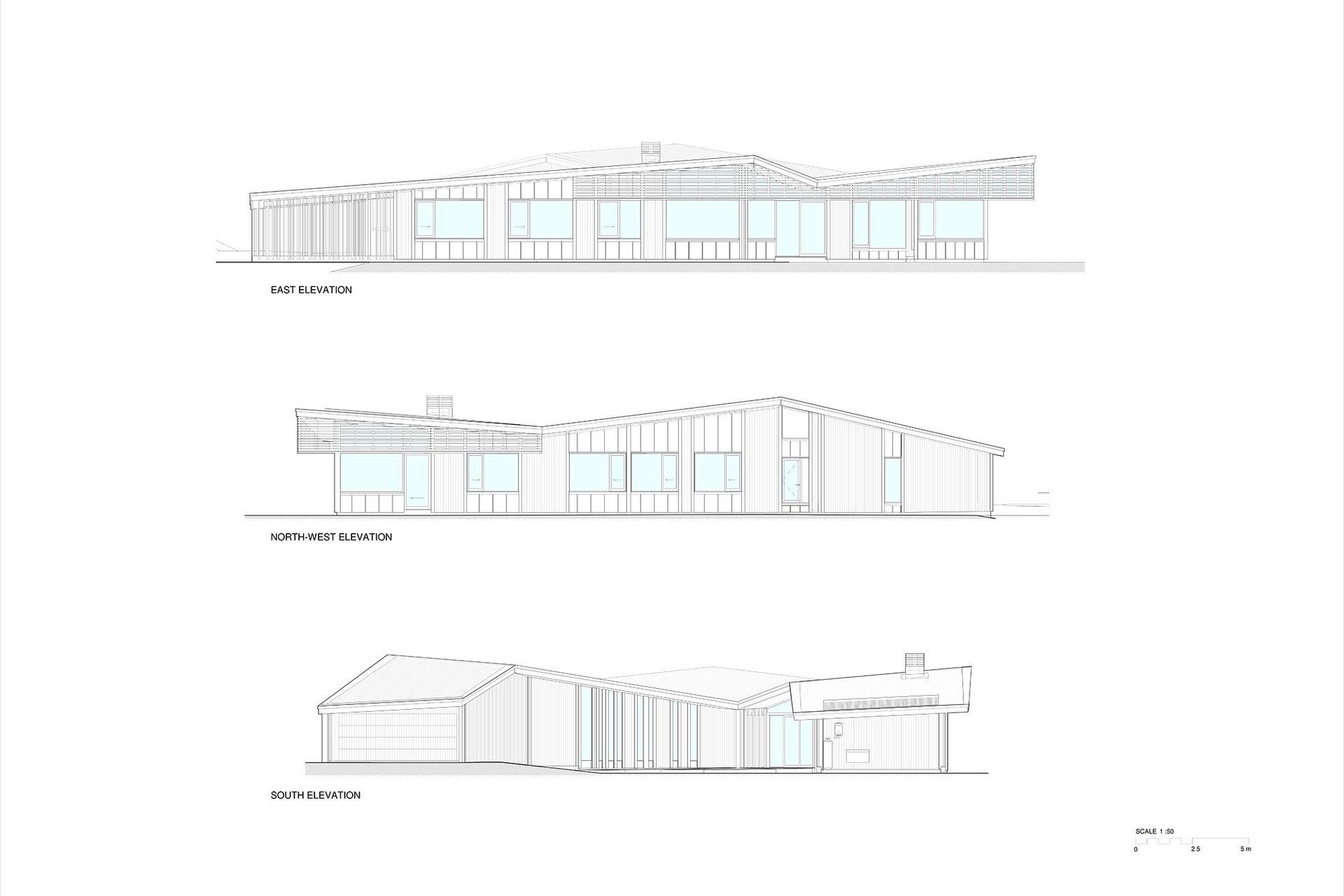

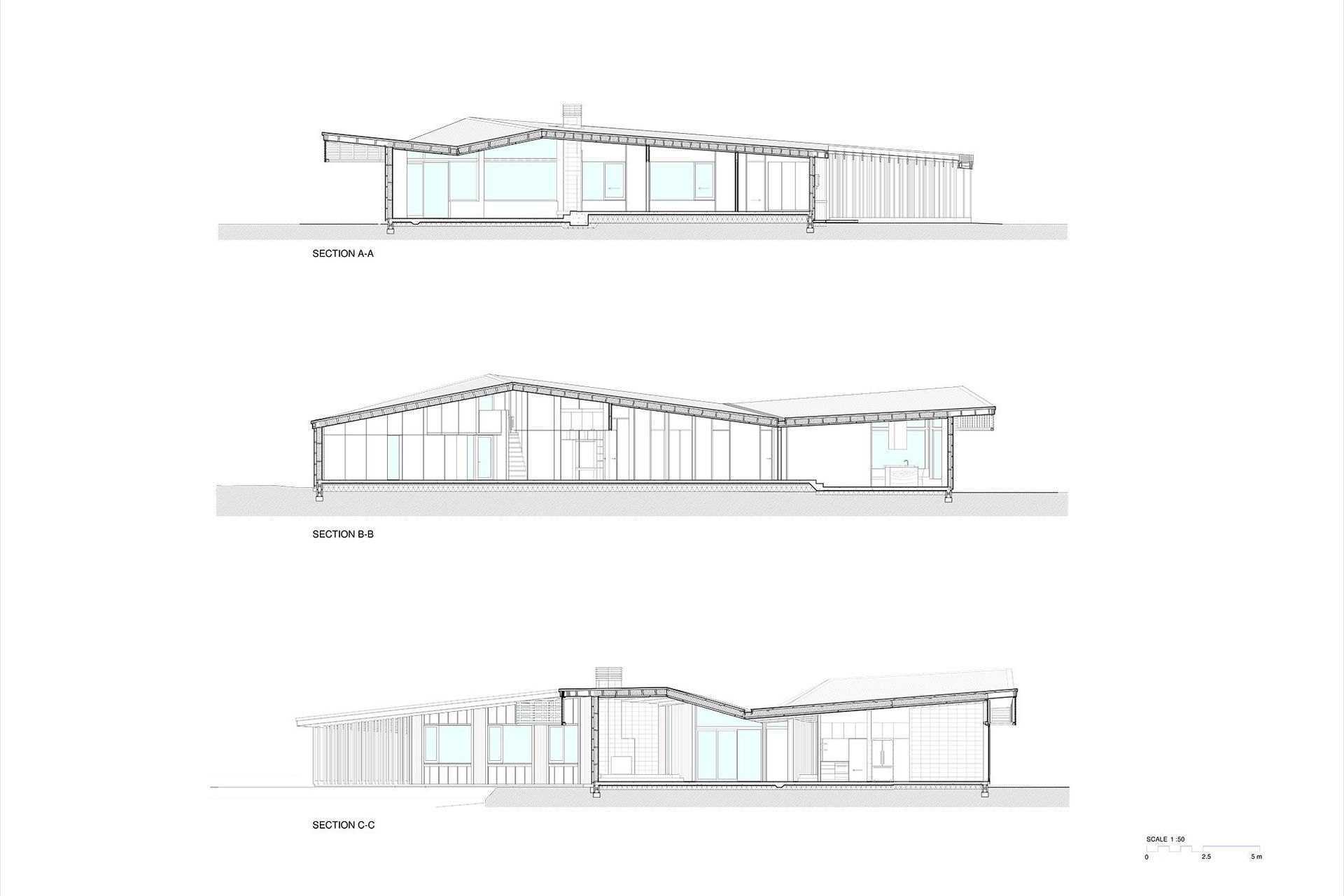

In spite of the climate, the homeowners – an anaesthetist and a doctor – wanted a comfortable and cosy home, so Gerald and his team set to work to develop a U-shaped building with timber slatting positioned to diffuse the wind as it runs up the glass on the windier side. “We did a lot of computer modelling of the house and thought it would work, but we had no real way of assessing it without wind testing – so we ran with our gut feeling!” says Gerald. “Although, both living and working in Wellington, we have had a lot experience designing for windy conditions.”

“Fortunately, it has all worked out really well,” he adds. “The slatting at the pointy north-western end of the building acts as a filter to slow the wind, working much like a sieve or the way trees filter the wind. The general principal is that a solid object accelerates wind on the windward side and makes the leewood side calmer, while the slats help to shelter the courtyard within the ‘U’ of the plan.” Meanwhile,

on the south-facing side of the house, a neighbouring tree-covered hill adds protection against the cold southerlies that blow in from the Cook Strait.

With these aspects in mind, this hilltop house wraps around the courtyard and the bedrooms are positioned in each wing separating the owners and their two older children to give them plenty of privacy, but so they can meet in the shared middle spaces around the courtyard.

Another key aspect of the design is its expressive roof form, which the owners were really keen to have. “Before we even started work on the design, they showed us images of houses with expressive roof forms that they liked, so we took their idea as inspiration and created a low-slung form that is slightly undulating – like the rolls of the neighbouring hills,” explains Gerald.

The result is a skillion roof that also helps to marry the house to its context. At some point in the history of this hill site, the top of the mound had been excavated, flattening its top, but, now, the architects have replaced the old hilltop with Ostrich House, effectively making the home become part of the landscape. The shape of this dynamic roof also adds drama and movement to the interior, accentuated by plywood ceilings which continue out into the eaves.

“To tie the house into the site, we used driftwood-coloured cedar for the external cladding because it weathers nicely and is low maintenance then we inserted vertical zinc panels above and below the windows,” says Gerald. The exterior cedar cladding on the outside of the hallway, running parallel to the main entry, has been taken into the house to form a cedar wall – blurring the inside and outside.

Ostrich House has also been designed to be as sustainable as possible. The architects have exposed concrete floor areas to the north so that when the sun in low during the winter, the sun shines through the windows and heats up the concrete slab and, because it’s a heavy mass element, it re-radiates the heat later on. “It’s a great way of achieving passive solar heating,” suggests Gerald. “The slab is under-insulated as well, so the heat doesn’t go out and into the ground.”

“We used low-E, argon-filled double glazing and thermally broken window frames,” says Gerald. “It’s a little bit more expensive than your standard aluminium window frames. However, with a standard aluminium frame that’s inserted into a good-quality double-glazed window frame, the heat or cold easily transfers through the metal from the outside to the inside so, quite often, you find condensation on the metal elements inside a house. But, thermally broken windows like these have metal on the inside and outside with a layer that separates them, so they don’t transfer the heat, preventing major heat loss and condensation.”

Because the house is located in a 'specific design' wind zone area, the whole exterior of the house has been ‘pre-clad’ with a layer of plywood underneath the cladding to prevent air leakage through into the house. “It is effectively a double protection against any leaks from air and water under pressure from the wind,” explains Gerald. “It helps to seal the house up so, when you’re in there, it feels quite solid and relatively quiet. We added a heat-recovery ventilation system too, which allows heat to be transferred from warm areas to cool areas and it brings in fresh area from the outside and heats it with the heat that’s recovered from the existing air that’s pumped back out.”

Creating a house that’s sustainable hasn’t in any way detracted from the look of this home, which slinks along the hilltop and provides a wonderful visual respite for any cyclists passing by. And, for the owners, it’s not only a warm and welcoming home but it offers incredible protection against the worst of Wellington’s winds.

Words by Justine Harvey.

Photography by Paul McCredie.