The brief was clear: not another box!

“The clients felt that the current Christchurch vernacular was quite a strong one but not one that particularly compelled them. The desire was to create a unique building very different to the standard rectilinear rebuilds increasingly dotting the Christchurch suburban landscape—they wanted to create a piece of sculpture,” says Nicholas Officer, Director at First Light Studio.

“The clients also wanted a property that offered more space for family and friends to visit and stay—a house for people to come back to.”

This is the fifth project on which First Light and their clients have collaborated, the previous projects being a mix of residential and commercial jobs, including the rebuild of an earthquake-damaged home.

“The clients are, themselves, involved in the industry and are people who respect design and what the architect brings to the process. Even so, this was quite a challenging project for us as a practice, as we’re usually quite pragmatic in our approach.

“We presented 12 designs, which were refined over a number of iterations before settling on ‘Shark House’. Our designs are usually site-responsive, ie: we design for solar gain/mitigation, shelter from prevailing winds, views, access and privacy. With this house, we designed for all of those things as well as for the clients’ desire for something sculptural.”

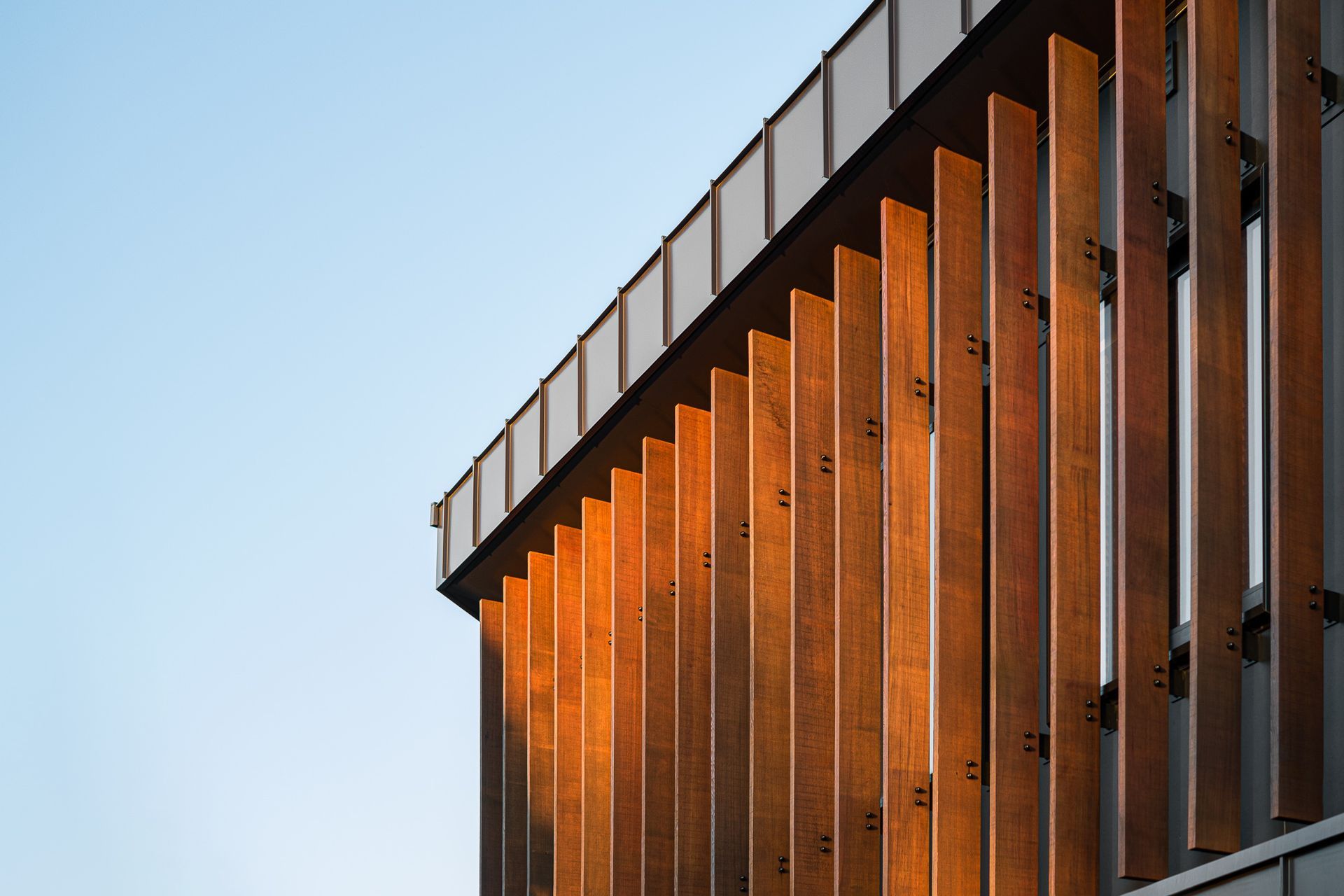

The resulting building is bold, confident and far from anything remotely resembling a box. ‘The Shark’, as it has colloquially come to be known, inhabits the site, in an almost rhythmically fluid sense as angular planes and crisp lines overlap and converge, twisting around the facade as if the building is forever in motion.

“We have drawn inspiration from the clients’ love of European supercars—particularly Maseratis—for the form and materiality, creating an interplay that, like its vehicular muse, seamlessly merges materials into one another without breaking the form or flow.

“No surface is perpendicular to any other yet this doesn’t seem haphazard, rather the offset faces and acute edges of seamed steel come together with engineered precision. A rich timber ‘grill’ wraps around the second-floor facade, serving to both soften the steel’s austerity and moderate solar gain over the course of the day.”

Inside, the material palette of timber and steel is augmented with a textural concrete core, which reveals the timber grain of its formwork, complementing and contrasting the timber soffits and ceilings. Strip LED lighting has been incorporated into the ceilings in a random pattern that heightens the theme of movement.

Programmatically, the public and private spaces have been divided along a horizontal axis with public spaces inhabiting the lower level and private, the upper level. Living areas are north-facing and span east to west—to capture all-day sun—and flow out onto lawned areas. Service functions have been placed along the southern boundary.

“We’ve taken a ‘first principles’ approach regarding ESD considerations—using the site to its maximum potential; incorporating passive screening etc.—and then augmented this with a number of mechanical devices such as solar panels and central heating. Further to this, we’ve ensured that the owners can ‘age in place’ by concealing a lift behind the board-formed concrete walls, minimising any issues to do with access.

“The project has been a real success in terms of arresting people’s attention, both here and internationally and I am proud to say it meets its brief and then some. It is a house of dualities: its entirely static construction of solid surfaces manages to achieve a dynamic fluidity, sculpted inside and out—presenting a hard and durable outer skin combined with an interior that is warm, comfortable, relaxed and inviting—much like the high-performance machines that have inspired it.”

Words by Justin Foote