Combining the Kiwi way of laid-back living with Asian architectural influences, Lin House is a unique fusion home on a constrained site in Remuera, situated about ten minutes from Auckland’s central city. This modern, energy-efficient home has been future-proofed to adapt to change on every level, including super-smart technologies that can be managed from any device, and solar panels that power the lighting and heat the pool.

Adaptability and a sense of privacy and retreat were essential requirements in the design of Lin House, a 330m² home on a tight suburban site within a neighbourhood of ’60s houses. Constrained by close neighbours on either side and the sunny northern aspect facing the street, Daniel Marshall Architects was faced with the real challenge of creating a unique, functional and light-filled home for a young family.

At Lin House, light and landscape press into the interior through glazed walls and openings, creating a comfortable and restful place to occupy. Nestled into its site, it feels more like a courtyard house than a suburban home, with a series of modest outdoor spaces that echo the Asian-influenced architecture.

“I didn’t want a huge section as I’m not a fan of mowing lawns,” says Henry Lin, who owns the home with his wife Coco and their nine-year-old daughter. “I wanted an apartment-like lifestyle but with more privacy. It was also important that Daniel design a house that I hadn’t seen before, because I had looked at about 100 houses to potentially buy but they all had a similar traditional structure, and I wanted a very modern fusion home with elements of Kiwi, Japanese and Chinese architecture all combined together.”

While Lin House finds its own unique contemporary identity, the gabled roof form is sympathetic to its suburban context. “Above the front fence, our new home has a traditional gable like the neighbouring houses, however the first floor has been cantilevered, which makes it look different,” Henry explains. “Then, along the side of the house, a pair of very large curved concrete walls into the garage have a different style, but the combination of the two elements creates something unique in this area.”

“Deliberately using the gable form is also about future proofing for climate change,” adds Daniel. “With increasingly heavy downfalls in Auckland comes the need to get water off the outside of the building as quickly as possible, so the house is designed to be adaptable to future changes, whether it be environmental, technological or occupant related. With design, you have to consider changes over time so we chose low-maintenance materials with longevity, and I’m obsessed with materiality and the effect of human touch on materials—like timber, concrete and stone—that develop a patina over time.”

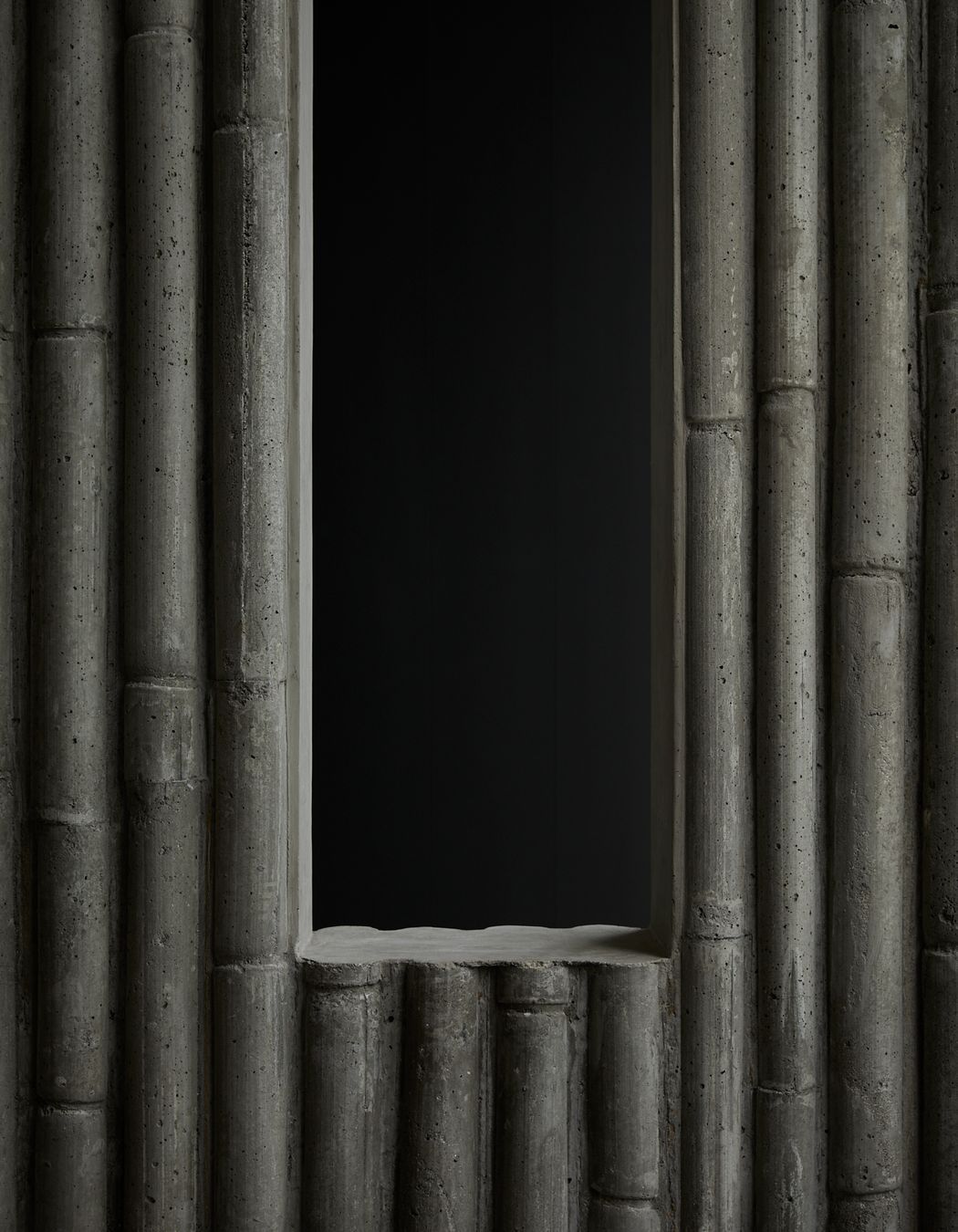

Another reference to Henry and Coco’s Asian heritage is a key feature of this home—the innovative cast in-situ concrete wall with a surface patterned in bamboo shoots—that runs from the entrance up past the upstairs’ balcony to the soffit. “The in-situ concrete wall was constructed using bamboo formwork, which has created a beautiful textural quality to the concrete,” explains Daniel. “The bamboo was cut in half so the concrete pattern becomes a positive. We think it’s the first time it’s ever been done in New Zealand.”

“It was a risky exercise to construct the wall, but hugely rewarding at the same time,” explains builder William Lindesay from Lindesay Construction. “It’s 7m tall and 2m wide, which is a lot of wet concrete placing pressure on the formwork so we were worried that it could have been crushed by the loads. But, we worked with an engineer to calculate the loads; we cut the bamboo open to reveal the internal face of the bamboo; then, created prototypes to test the formwork with foam filler in behind the bamboo to help support the formwork. This process took three weeks and some tests failed miserably and while it was a calculated risk, we managed to pull it off.”

About 80 per cent of the house was formed with precast concrete, except for the bamboo concrete wall and curved forms on either side of the garage, which were cast in situ. The curves enable an effective car turning space off the driveway while, internally, the walls mimic the curves to create flowing spaces in the scullery, laundry and several bathrooms, adding subtle details to the geometry of the building.

Because the house sits on a relatively narrow 18.4m-wide section that faces north to the street, it made sense to site the pool area and the main living areas at the sunny front part of the property. However, this meant there was no room for a garage at the front. Fortunately, Henry wanted to avoid a home that was estranged from the street. “Garages at the front can be very dominant and take over the street but, by moving the garage down the side of the house, we were able to utilise the front part of the section,” says Henry. Here, the main living space flows out through big sliding doors to the pool and spa area. “It creates an extended space when it opens up—it actually feels like the living room has doubled.”

Inserting the car garaging into the middle of the ground floor also created separation between the main living areas and the guest bedroom suite. “The guest wing is private and works well for the owners’ parents when they visit or for the daughter to use when she is older—and it also means the house can easily be turned into two homes in the future too,” Daniel explains.

With limited outdoor space, it was important that the courtyards were fully usable. “Because they’re quite leafy and green, they don’t feel like small areas. You actually feel like you’re in little park gardens,” says Henry. Along the eastern boundary of the property, just off the dining space, a 'lineal’ courtyard is edged in bamboo and meanders past a chunky concrete bench seat with a built-in ethanol fireplace. “That was inspired by the dramatic entry to the Nezu Museum in Tokyo by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma," explains Daniel. "The entry to the gallery just had the monumentality of the gallery wall framing the walkway, with actual bamboo as a border between the entry walkway and the street." At the rear of Lin House, a timber-decked courtyard leads into the guest wing and features a specimen maple tree that takes on a sculptural quality when lit up at night.

Upstairs, there is a study and two bedrooms with ensuite bathrooms, and a master suite that cantilevers over the front courtyard, giving shelter to the front courtyard. The master bedroom and balcony enjoy views of the neighbouring trees looking all the way down the valley towards Orakei Basin.

In the heart of the home, a classic Kiwi galley-style kitchen was designed for Asian cooking with a full chef's set-up in the discreet scullery in behind. “This is typical of Chinese kitchens, where all the hard work is done behind the scenes,” explains Daniel. Covetable features include a super-convenient tap over the hob to fill saucepans with water, and a Sub Zero fridge that preserves food for three to four times as long as a normal fridge by using NASA air purification technology that slows down the growth of bacteria, moulds and viruses.

Henry’s love of technology is apparent throughout Lin House, with a fully integrated system that means lights and security are easily managed from a smart phone or device. The home is also highly energy-efficient with heavy insulation; double-glazed, thermally broken windows; and a solar power system that powers the LED lights throughout the home and the heating of the pool.

“Henry especially loves the solar power because the power bills are now about $30 and he can leave the lights on as much as he wants,” says Daniel. “As well as being sustainable, using an alternative power supply like solar is also about having a security of supply and reducing our reliance on corporations. In fact, we’re finding that more and more homeowners want to invest in solar battery storage as well as the panels, so they can charge them up to power the home at night and sell any excess electricity back to the national grid.”

While Lin House is a comfortable and adaptable home that’s set up for the future, Daniel believes that, right now, there are a lot of interesting questions we need to be asking about how our architecture is being designed and built. “Due to the coronavirus and the environmental and economic factors we’re currently facing, I think the tide may wash back out of our urban areas and people will look at living in smaller cities and more suburban areas. We will be designing for this new world of physical distancing, as well as ensuring sustainability, health and hygiene are an absolute given, not a nice-to-have. It’s certainly a time of change that we need to make positive.”

Words by Justine Harvey.

Photography by Sam Hartnett.