Ka kōrekoreko ōku karu i te tini o ngā whetū i tuarangi. (PK 2088:988)

'My eyes are dazzled by the multitude of stars in space.'

_____________________________________________

Tuarangi house didn’t exactly fly in from outer space but it’s certainly not your typical Grey Lynn villa, with its angular roof and walls that jut outwards to the Waitakere Ranges on the horizon and up to the sky.

It comes as no surprise that this is the home of a designer. It belongs to the young family of Craig Wilson from TOA Architects, who commissioned his TOA director Nick Dalton with the task of designing a home for him and his wife Kristin and, during construction, their young son Ezra joined the whanau.

“We studied together at Vic (Victoria University of Wellington) and, then, worked together, where we discovered that we have a similar design philosophy and aesthetic,” explains Craig. “During the concept stage, we did a lot of research into Tuarangi Road and discovered that Tuarangi’s meaning in Maori is ‘outer space’, but we couldn’t find out why the road was called Tuarangi, so that is still a mystery we would like to uncover.”

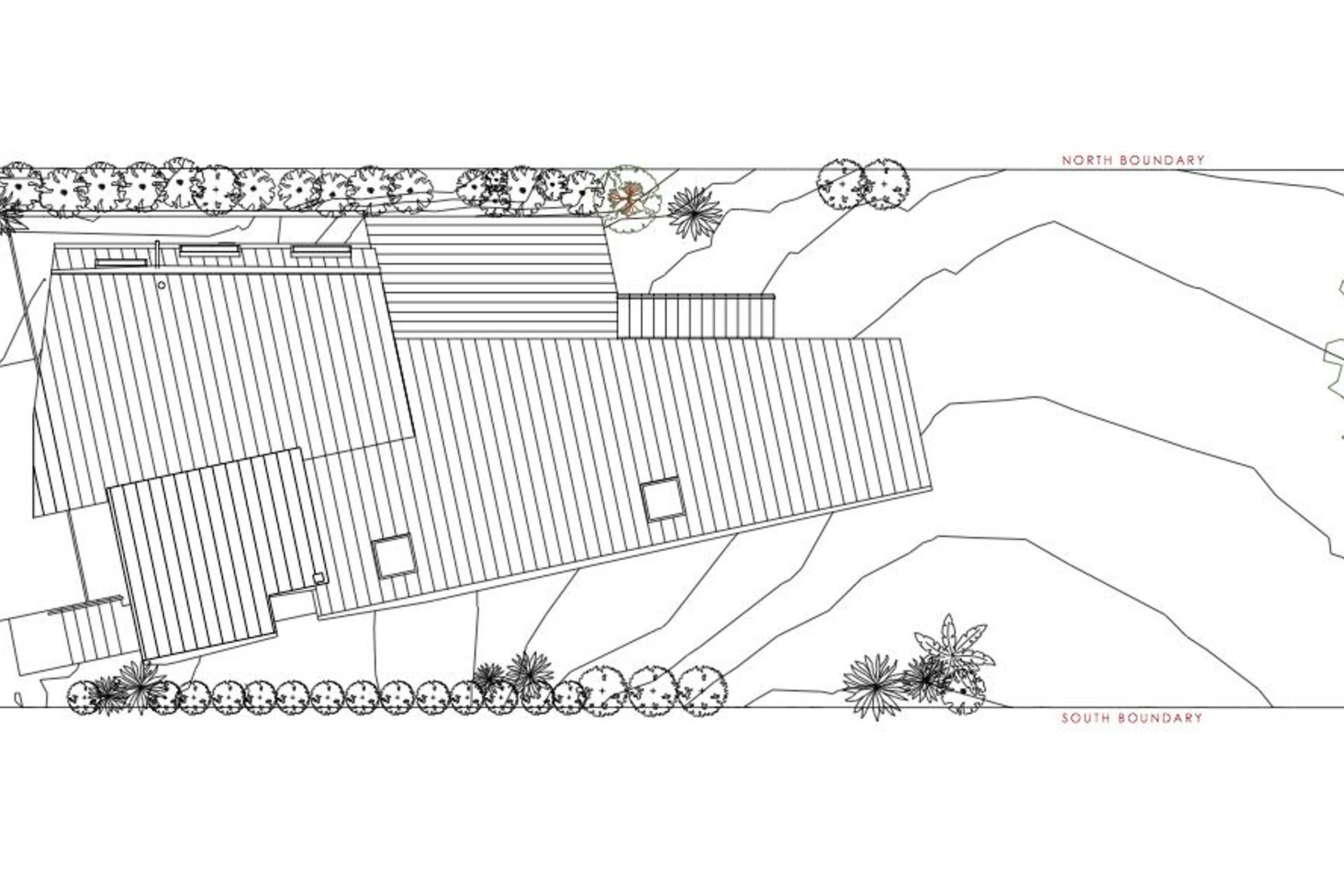

This steep and narrow plot is also intriguing in that it contains a slight gully that runs across the back garden and into the neighbouring properties, which makes you wonder if a stream once trickled through it. A small grove of fully established trees adds a sense of history to the site. “We were careful to retain some of the existing trees on the site, including a huge vintage plum tree, because they create a beautiful backdrop to the house and add focal points to some of the internal views outwards,” he says.

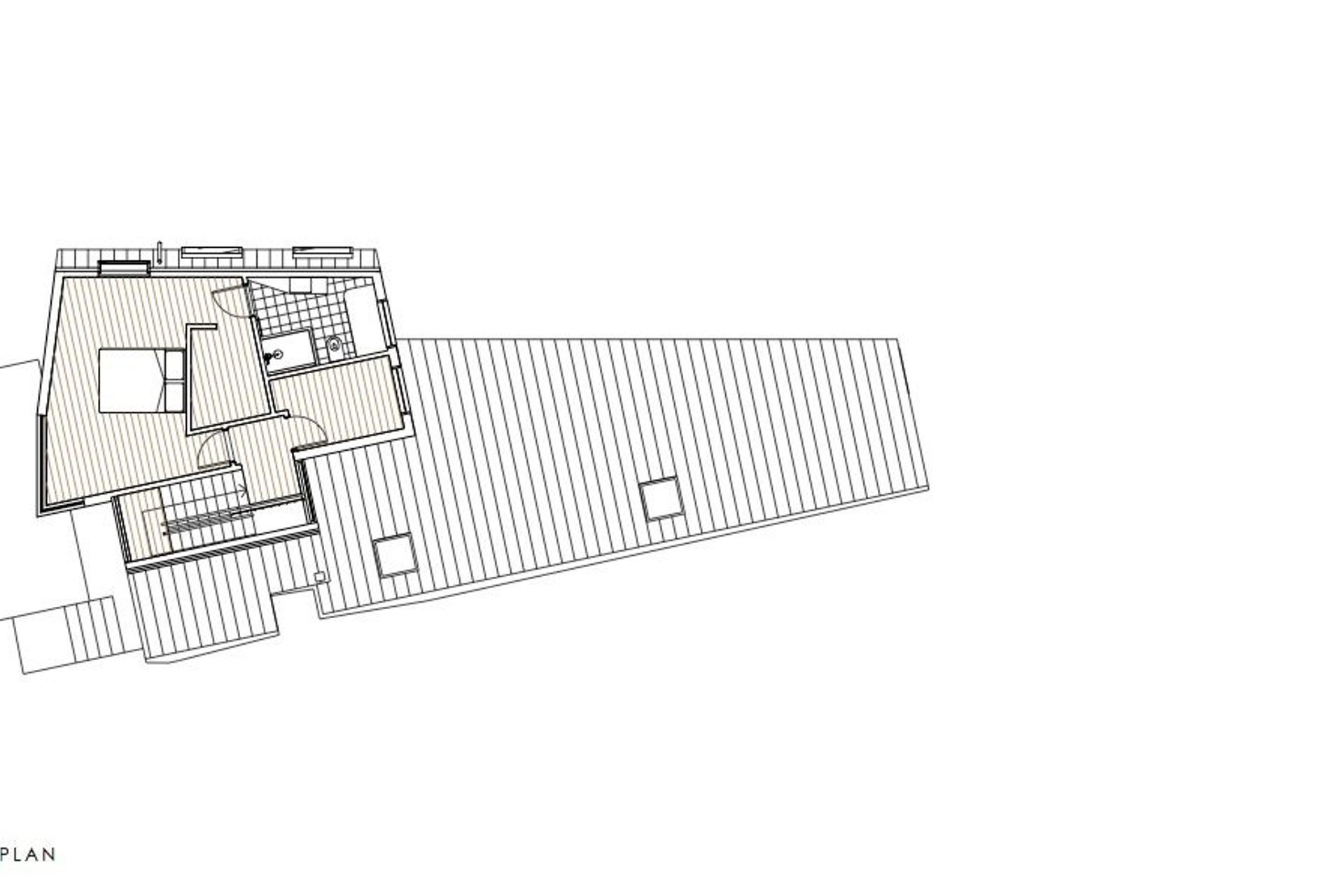

A window facing the plum tree and the rear garden is a particularly special feature. This nautical-like port hole pays homage to two godfathers of New Zealand architecture, Sir Ian Athfield and John Scott, who were big fans of port hole windows, frequently incorporating them into their designs. The wall in which it sits also services the pipework from the upstairs bathroom and toilet.

On the upper level of this two-storeyed home, a sharp corner in the master bedroom features a glazed window that juts out into the street and offers a view to the Waitakere Ranges along the horizon. In this room especially, one has to wonder if the builder must have cussed the architects a few times while trying to achieve all the angles in this design. Apparently, there are only a handful of right angles in the entire house and the front façade appears to fold in on itself, creating a diagonal facet facing the street.

Part of TOA’s mission is to streamline the building process through prefabrication methods (see The Mana of Multi-housing) so, in the same vein, Tuarangi is a well-researched experiment by the architects. Its walls, floor and ceiling are constructed in 43 panels of cross-laminated timber (CLT) that is manufactured from New Zealand pine and can span long distances, and insulated concrete formwork (ICF), greatly simplifying the building’s structure, construction timeframe and waste. The superstructure was erected in 10 days from the foundation up.

“We were really keen to use it as a new technology and to push it as far as we could go,” says Craig. “One of the largest panels is 14.4m long and the process meant that we could construct the house really quickly.”

It’s also exciting to see an interior cladding in New Zealand pine that looks cool but is more budget conscious and sustainable than most other timber claddings. Here, the tone of the timber is much lighter and softer than was fashionable in the 1970s when varnished pine interiors were de rigueur but delivered a particular brassy effect.

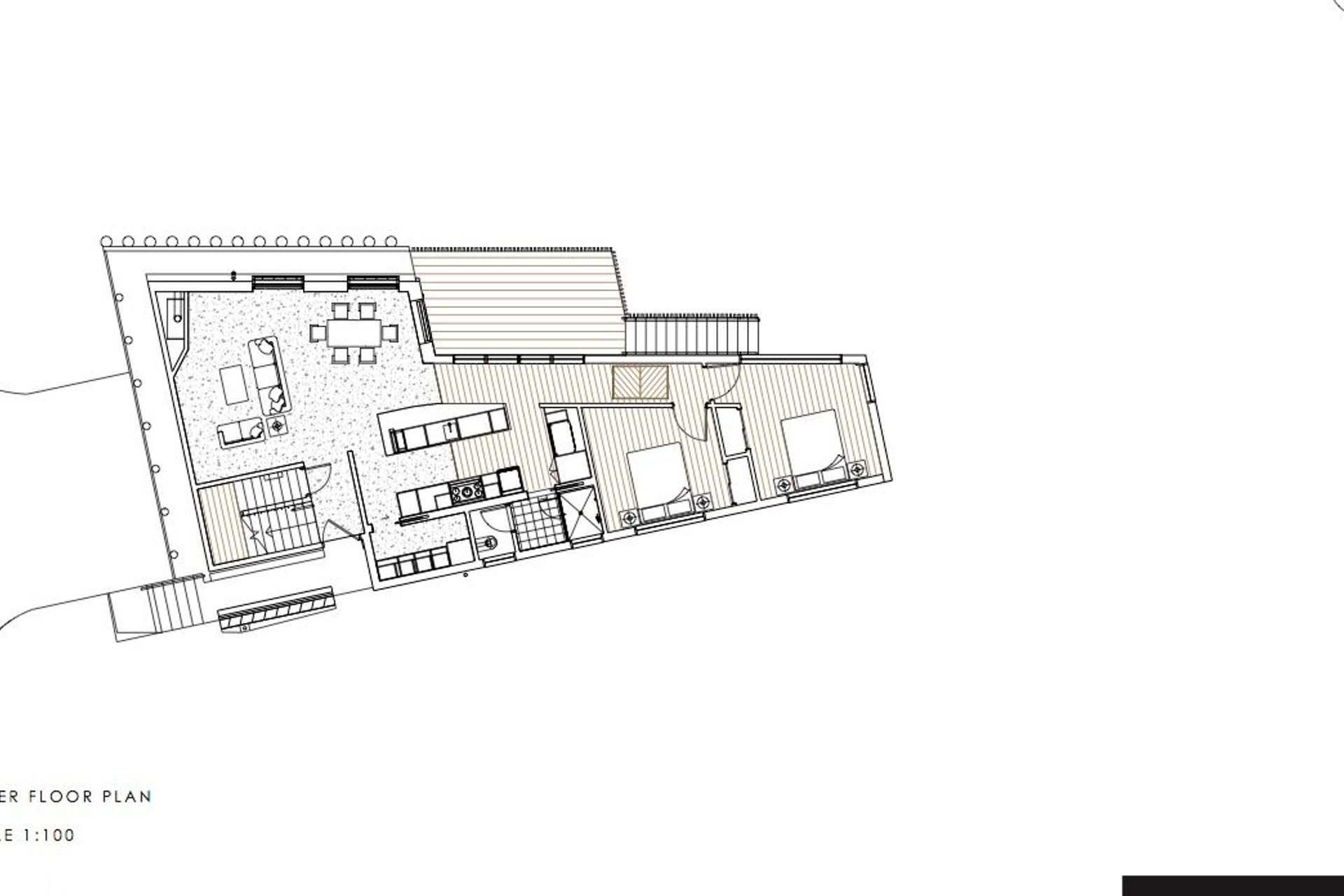

The main space in the house is an open-plan living/dining/kitchen area that flows out through a black steel sliding door onto a timber deck that leads down stairs to the rear garden. An interesting detail on the deck is the balustrade – the latest in a series of iterations designed by TOA – which features upright posts seemingly held together by a single steel rod. Along the top, angled tips have been expertly painted in colours influenced by the green and blue feathers of the local tui.

The kitchen bears Craig's elegant design aesthetic and passion for good food and wine (he grows hot chillis and is renowned for his home-made super-fiery chilli sauce). But the gem in this kitchen is the faceted-fronted island, which features a piece of polished swamp rimu slotted up against a charcoal-grey stone benchtop. To the side of the kitchen, a scullery/laundry hides all of the detritus of washing up.

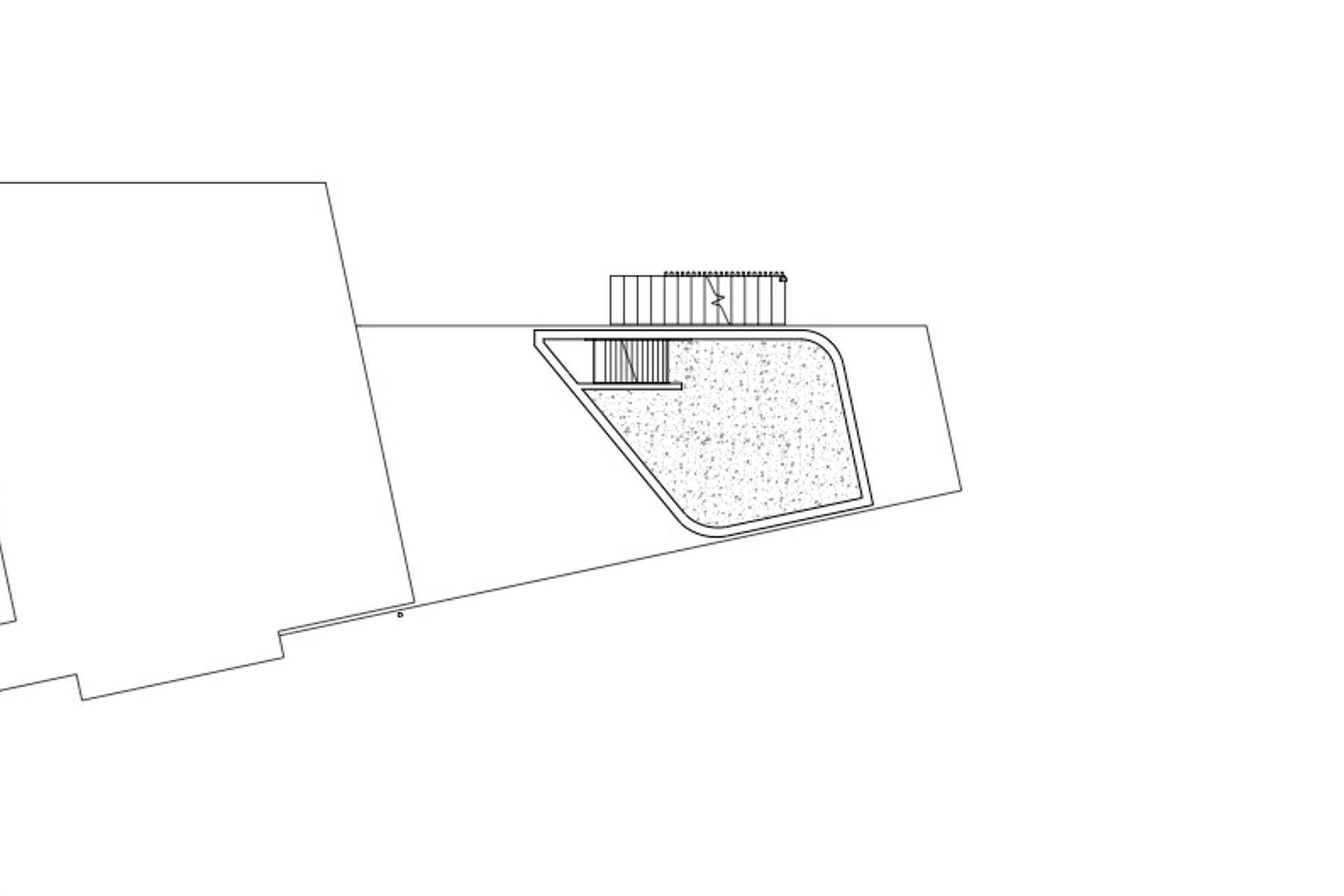

Along a corridor from the kitchen, a large trapdoor in the timber floor opens up to reveal a staircase that descends down into a decent-sized wine cellar. This part of the house is a work in progress with plans to have a sofa down there for relaxing in during private wine tastings.

The form of the house tapers towards the rear to fit into this steep and narrow site, which also forces the form to cantilever out, creating a lovely light-filled space with a view over the rear garden. This room was originally designed as an extra lounge for Craig and Kristen, but it has since become a multi-purpose space that is currently being used as a playroom for young Ezra.

Another highlight of the home is the staircase, which is a real delight when you look up to the ceiling – where angles create distort perspectives from every direction. Here, a festival of timber is enhanced by the shadowy effect of sunlight that spews in from the north-west in the afternoon and south-east in the morning.

The exterior is clad in rough-sewn Douglas Fir from Abodo that’s been blackened by a coating of iron vitriol, which reacts with the tannins in the timber and causes a chemical colouring on the surface of the timber, helping to create a protective layer against the elements, while allowing the timber to breath. The technique that’s been adopted in Scandinavian countries for hundreds of years but has rarely been used in New Zealand until recently.

“I’ve seen iron vitriol-treated houses in Scandinavia that have survived for hundreds of years and while, perhaps, they haven’t encountering the humidity and heat we experience in Auckland, they do contend with extreme climates over there,” says Craig. An added bonus is that the treatment dries in about 24 hours and creates a gorgeous blackened timber finish.

While Tuarangi was under construction, Craig and Kristin lived in an old house on the site, which Craig describes as like “a little shack you’d find at Murawai Beach in the 1950s”. Here, the couple endured four years of freezing winters but, today, in their new home, they feel blessed. “We love it!” he says. “As an architect, one of the anxieties of a project you’re designing is that you believe it will work on paper but it’s not until you actually build it, when you realise that you have things generally right. This usually happens when the structure goes up and you’re standing in the space. I remember Nick and I standing in what was just a timber box and saying, ‘This space is really, really cool’. We realised that we may have nailed something.”

Words by Justine Harvey.

Photography by David Straight and Craig Wilson.