An open, super-functional kitchen and entertaining space were crucial to this simple timber-clad retreat in Little Akaloa, which was designed for a chef and lovingly built by his own son.

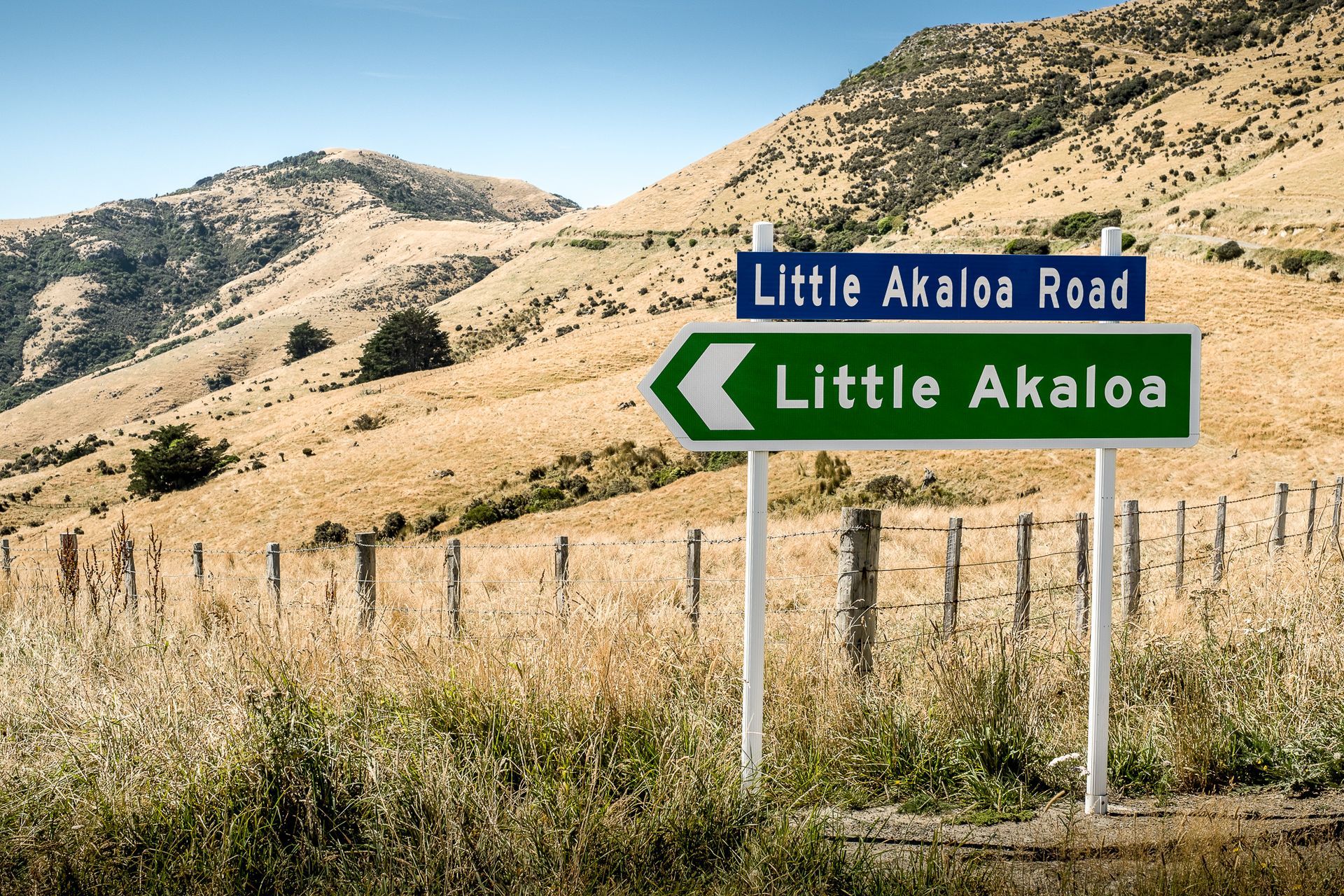

Before the Canterbury earthquakes, while visiting friends on the Banks’ Peninsula, the owner fell in love with the small settlement of Little Akaloa. It’s no wonder because this wee historic town has a lovely valley feel to it, being surrounded by rolling hillsides and overlooking a horseshoe-shaped bay filled with varying shades of turquoise ocean.

While its normally hard to find new properties in this area, he was lucky to discover a recently sub-divided piece of land and snapped it up to build a retreat for himself, and to draw his grown-up children back from living overseas for holidays. An implement shed was soon installed on the property but several years passed before architectural designer Ben Brady came onboard to design the home.

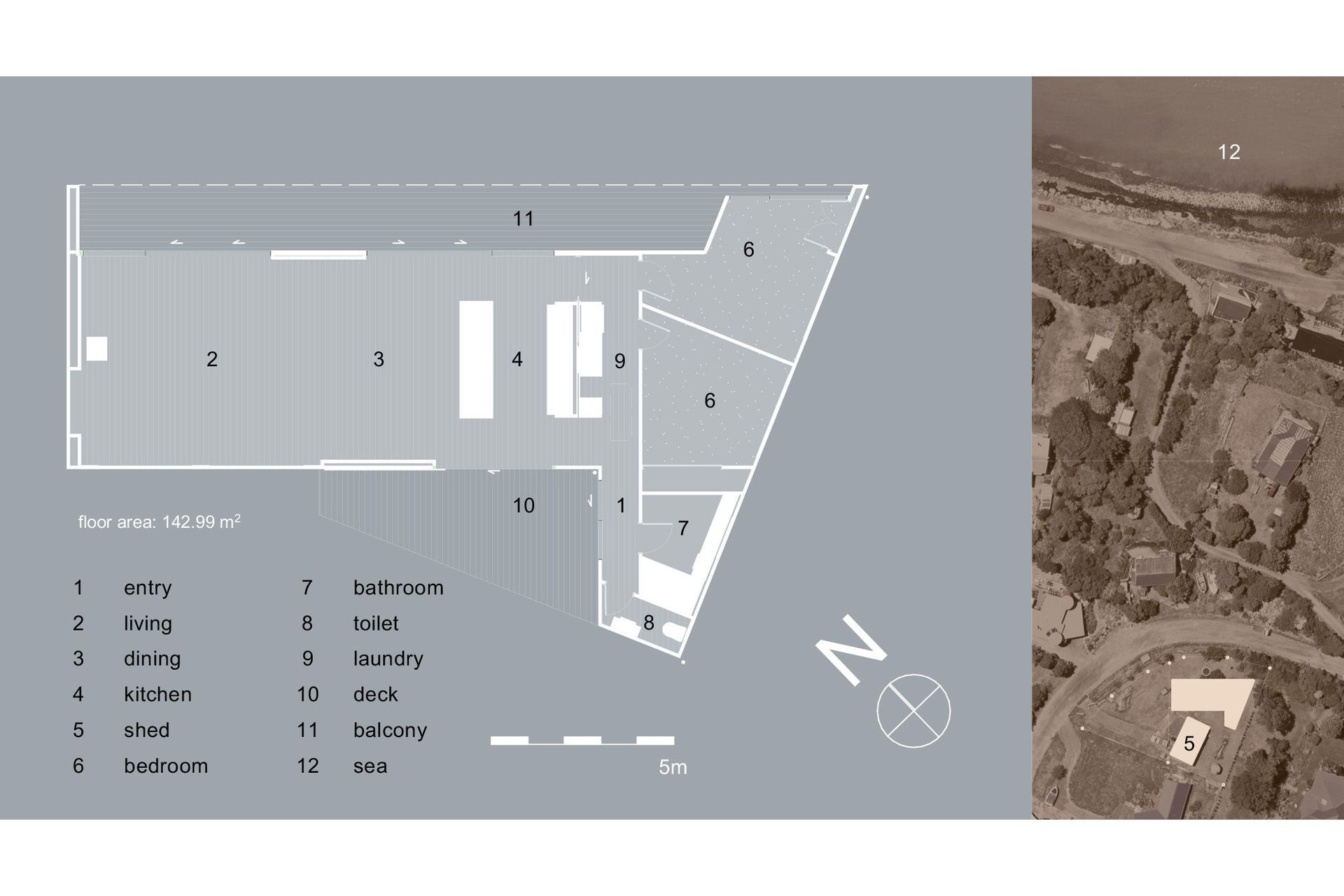

“The owner wanted to make as much of the view as possible, so we inserted the house on the top of the site as a pavilion form with an extension out the back and a simple gesture outwards – a wide-screen aperture to the sea,” explains Ben, founder of Linetype Architectural. "We were aware that the underside of the house was going to be quite visible from the access to the site, so we had to think carefully about how we treated the underside of the building. We kept the structure clean with the use of a couple of simple steel frames and cantilevered the floor beyond in both directions.”

The western elevation, facing the valley, is more enclosed: making a showcase of the timber cladding and a huge metal sliding door that opens up onto a deck. This is the perfect place to enjoy the evening sun, out of the cool sea winds.

Siberian Larch timber was chosen for the cladding as it silvers off over time, complimenting the colouring of the grasses on the Port Hills. Both the larch and the corrugated Colorsteel Maxx roofing minimise any maintenance. The aperture or balcony that looks to the ocean is lined with horizontal cedar and all the timber is fixed with battered nails, adding an interesting finishing touch. “Because it’s a simple form, careful attention to the details really drove the design," remarks Ben.

He says the owner and his family are 'tall' people so, internally, he made the ceiling high – at 3m high – and the layout is very open, which ensures the space feels generous and lofty.

“The house is very simple and feels like a bach should; it’s not trying to be ostentatious,” he explains. The layout is open-plan with the living/dining/kitchen area taking up most of the plan, a laundry in behind the kitchen and two bedrooms tagged on the end. An offshoot space – like a lean-to – accommodates the main entrance, bathroom and toilet.

The owner and his family are highly creative so they designed the interior fit-out themselves, making a show of their combined interest in art. “The owners have a nicely curated art collection with contributions from all members of the family, so they have selected things that give the right feel and gestures for who they are,” comments Ben. On display in the living area are a giant iPhone sculpture and a set of schoolhouse chairs with crocheted socks on the bottoms of the legs to prevent any damage to the oak flooring.

As you’d expect from a chef, the kitchen is arranged and geared up for cooking. Some of the pots and plates are open on the shelves for easy accessibility, and the gas cooker and sink are inset into the island. This is a different arrangement than is typical, yet it’s practically designed so the chef can enjoy the ocean view when standing at the cooker.

“Unlike a lot of modern kitchens, this kitchen is not apologising for cooking,” says Ben. “Architects talk about ‘honesty of materials' but we also need to think about ‘honesty of use’ as well. The design process can be a weird thing because clients aspire to some of the glossy magazine photos they see but, in reality, to be liveable, the vision needs to take into consideration the actual use of the space. Get it wrong and you end up building two kitchens – one for display and one for use.”

At Sea Call, the owner asked Ben to insert a large industrial metal door to the side of the kitchen; however, since he couldn’t find one off the shelf, he had to design it himself and have it custom-made instead. It was then hung off an industrial-grade track, by CS Doors, that can hold a door weighing up to 500kg. The insulated door leaf is clad in pure zinc, and all the rivets and seams are expressed as they would be in utilitarian industrial design.

It seems apt that this popular ‘industrial look’ is being used in contemporary rural houses, with Sea Call clearly paying homage to the corrugate and timber sheds you see strewn around the New Zealand countryside.

In his Christchurch practice, Ben has been seeing more demand for modern country homes. “I’m really trying to push the artier side of the ‘contemporary rural’ vernacular,” he explains. “The traditional gable form, although beautiful, has almost been done to death now – it’s kind of the playschool concept of what a house should be, I think, so I can see its appeal. These days, every time I go out into the countryside, I’m becoming much more excited by the asymmetry of shed forms, with their ad hoc lean-to additions, than the more ‘urban’ interpretation of a farm house.

Photography: Dennis Radermacher/Lightforge Photography